| |

Expeditionary Navigation In The Arabian Desert

Not all expeditionary navigational problems are created

equal, and your approach to navigation varies with terrain,

capability of the vehicle, and degree of access to the

land. Limited access makes navigation more

challenging, and unlimited access gives you hundreds of options when you

plan your expedition.

Most regions of the developed world place major restrictions on what you

can do, where you can go, and the amount of permission required to

undertake your trip.

The Saudi Arabian

desert is different. You have unrestricted access to the desert once

you are outside major metropolitan areas. When you are

fifty kilometers outside of Riyadh, you can travel off road for 500 to

1500 kilometers in any direction. You enter the desert wherever you

please, and you exit the desert at will. Furthermore, the Arabian desert does not contain land mines, and there are no civil wars

to complicate off road adventures.

Principles of desert navigation vary according to where you make your

overland trip. Many locations require you to travel on

well-defined tracks, and figuring out your location is as simple as

reading your odometer to see how far you have progressed down a particular

track. Large areas of

the Arabian Desert have no tracks. You simply head cross country

with the only limits being imposed by geographic obstacles such as

escarpments and mountain ranges. To a large extent, the amount of

fuel you carry and the time available determine what you can accomplish on

your expedition.

in highly developed countries, navigation involves keeping track of

your position as you drive on known routes with lots of landmarks.

In the Arabian desert, navigation is more like navigating at sea.

Wide open spaces and few landmarks guide you as you

explore a sea of sand.

SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

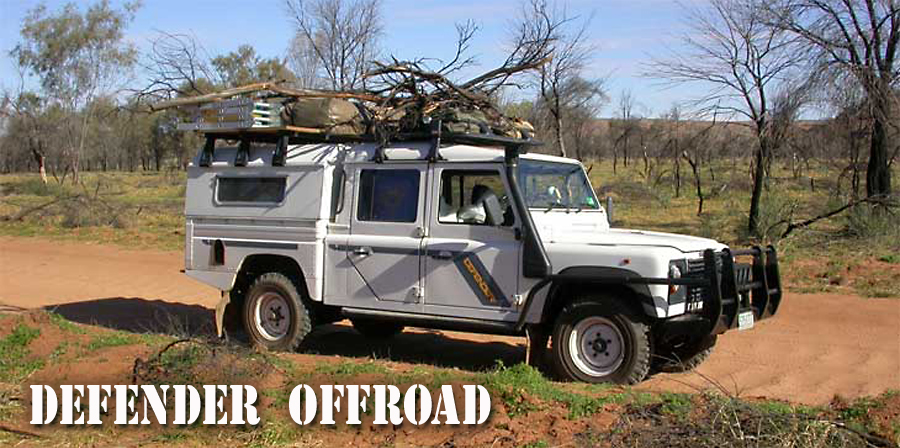

Situational awareness forms the foundation of successful expeditionary travel.

Situational awareness means that you know yourself, your vehicles, and the

desert in which you travel. You must know your vehicle well

and understand its capabilities and limitations.

Each year that I lived in Arabia,

I read stories in the newspaper about people who died in the desert

because they were not situationally aware.

Joshua Slocum, (the first man to sail single-handed around the world)

said, "You must know the sea, and know that you know it, and know that it

was meant to be sailed upon."

A similar statement could be made about desert expeditions. "You must know

the desert, and know that you know it, and know it was meant to be driven

upon."

When you head into the desert, you have to understand what you are doing.

The desert is unforgiving to the unprepared, and a demolition derby awaits

those who know not what they do.

If you have a well-prepared vehicle with plenty of fuel and spare parts,

and if you understand the terrain and navigational problems associated

with your expedition, you will have an awesome adventure.

ROUTE FINDING AND NAVIGATION

The minute you leave the asphalt and enter the desert, you instantly

discover the difference between route finding and navigation. I

never understood this difference until I went on an expedition into the

Arabian sands. Route finding is different than navigation.

Navigation is about where you

are and the general direction you need to travel to reach your destination.

Navigation involves the big picture of your trip from start to finish.

Route finding focuses on what is happening in the next 100 to 300 feet in

front of the vehicle. Driving in the dunes and soft sand is a two

person job. The route finder sits up front with the driver and tells him

what is ahead. The driver concentrates on driving safely through the next fifty

feet. The route finder tells the drover to turn to the right, to the left,

to continue straight, or to stop

because of conditions directly ahead.

Although it's possible for

a solo operator to do both the driving and route finding, it can be exhausting and difficult work

in challenging conditions.

When driving in soft sand with lots of hummocks and in short closely

spaced dunes, you have to zig zag a great deal. It's much easier to have

one person doing the route finding through the sea of sand, so the driver

can concentrate on getting the vehicle successfully through the next

fifty feet of wily desert terrain.

Navigation is about the big picture, and route finding is navigation on a

micro scale.

Even when you travel on a Bedouin track, it helps to have a route finder

spot rocks and cross tracks that can destroy a vehicle's

steering and suspension.

Two Bedouin tracks crossing at ninety degrees

to each other can cause a lot of damage to your vehicle. The cross track

sometimes is elevated like speed bumps or depressed like ditches, and if you hit

them at speed, you can bend steering components and traumatize your

suspension. Unsecured gear in your truck may go airborne. I

know of vehicles that have had unsecured flying gear come forward and

crack their windshield.

The route finder warns

about hazards on the track so you have time to safely react. The driver

looks at challenges immediately in front of the vehicle, and the route finder

warns about dangers 200 to 300 feet ahead. A good route finder makes

the driver look like a professional, and a poor route finder makes a

driver look like an idiot who always gets stuck and frequently damages his

vehicle.

Route finding is micro navigation. The route finder records GPS

waypoints, courses, distances, geographical features, Bedouin camps, and

any other data that could be helpful if a problem occurs. We

always record the location of Bedouin tents in remote areas of the desert, because

if things go badly, Bedouins would be a big asset in a true

emergency.

We once came upon a serious accident in the desert where young expatriates

had rolled their vehicle. Saudis graciously loaded the most

seriously injured individual into their Land Cruiser and took the victim

to the hospital because the ambulance refused to go into the desert to render

assistance.

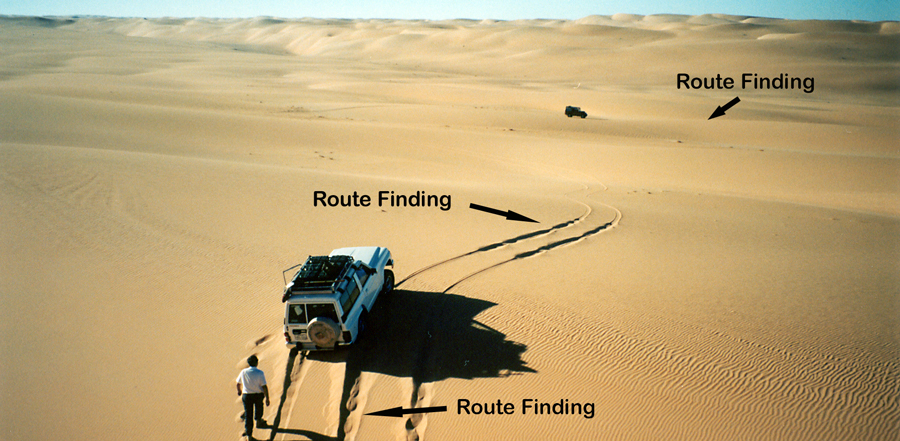

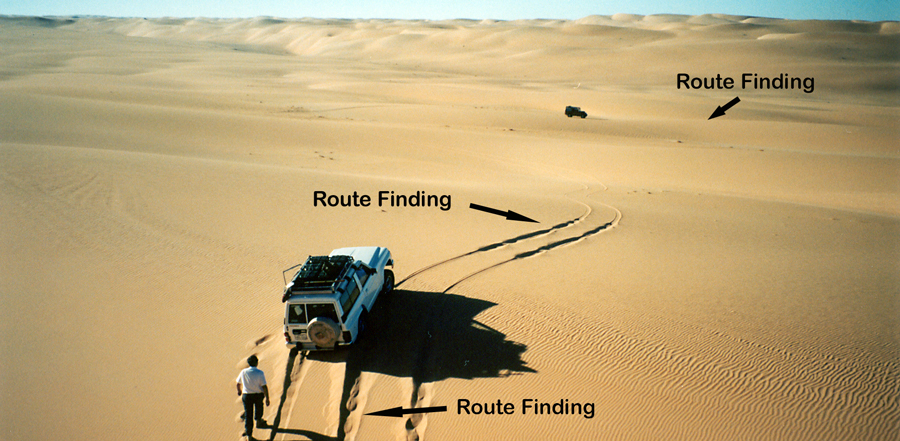

Route Finding

Route finding informs the driver of what he

or she should do next. Route finding usually deals with what is in

front of the vehicle, but occasionally it focuses on what is behind.

In this picture, the Nissan Patrol did not make it out of the sand hole,

and the driver got out of the car and walked back in the track to test the

sand behind the vehicle. The Nissan could go directly backward, or

could back up to the right or left. The driver tested the sand by

walking on it in different areas behind the vehicle. Once he

discovered an area of firm sand, he backed his vehicle onto that patch and

used it as his launching pad to escape his sandy

prison. In this case, he discovered firm sand directly behind the

vehicle, and the Nissan backed straight up. Next, he put the

accelerator all the way to the floor and said good-bye to the sand trap.

In front of the vehicle, route finding reveals a short patch of soft sand

on level ground. With enough speed it should be fairly easy to get

through that patch without bogging down as long as he transits the area

with gusto. Beyond the soft patch, the sand is firm all the

way out to the Defender parked in the distance waiting for the Nissan to catch up.

It's not by chance that the Defender is parked on a

gentle down slope. Fully loaded expeditionary vehicles always park

on a down slope so they won't dig in and get stuck when they start to move

once again. Parking on an upslope is a big no no, and is the sign of

a novice in the desert sands.

Navigation

Navigation is the big picture of

your expedition. It shows what you plan to do, and reveals the

contingencies available if things don't work out. It allows you to

define your navigational problem in concrete terms. You plot

distances and directions on the map, and calculate fuel requirements for

all contingencies.

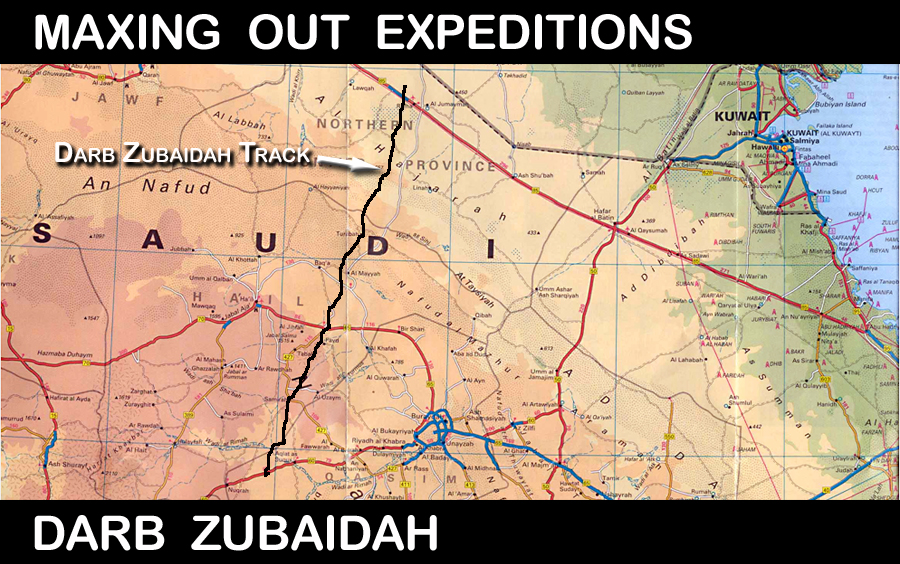

The map of the southern Nejd Quadrangle of Saudi Arabia contains a

smorgasbord of expeditionary adventures. I have driven thousands of

kilometers in this quadrangle. Each line represents a different trip

that starts in Riyadh. The white lines are highways that define the

entry and exit points into the desert. The thousand foot high Tuwayq

escarpment runs north to south for more than 900 kilometers on the right

side of the map. The granite fields are in the center of the map.

The lava fields (harrat) are on the left side of the map.

Lava, granite, and escarpment define what is impossible, and white roads

and colored desert tracks scratch the surface of what is possible to

accomplish in

this quadrangle.

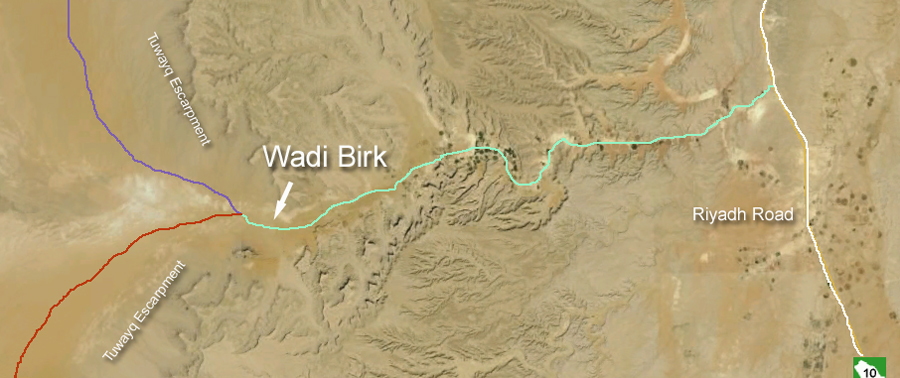

The red track cuts through the Tuwayq escarpment at

Wadi Birk and heads south west on sheet sand and low dunes curving over to

the tombs of Bir Zeen. The purple track takes you to the granite

mountains of Ibn Huwayil and Jebel Sabah. The light blue track takes

you from Khamsin to the tombs of Bir Zeen, and then through the lower, middle,

and upper granite fields with optional stops at Ibn Huwayil and Jebel

Sabah. The dark blue track explores the upper and middle granite

fields before heading north to the Mecca Road. The green track comes

south from Riyadh west of the Tuwayq escarpment on gravel

plain and sheet sand.

To reach the light blue track from Riyadh, you either travel 200

kilometers west on Mecca Road (Highway 40) before turning into the

desert, or travel 600 kilometers south from Riyadh and pass through the

town of Khamsin before entering the desert and heading north toward Bir

Zeen on the light blue track.

When you navigate in the southern Nejd quadrangle, the first thing you

need to do is define

the entry and exit points for your trip. The Tuwayq escarpment limits your

options on the east side of the quadrangle. You can pass through the

escarpment in at least three places where large wadis cut through the

Tuwayq. Another option is to do an end run around the escarpment at Khamsin

by traveling south for 600 kilometers on paved highway. If you want

to do most of the trip off road, you can follow desert tracks south for

500 kilometers after you leave Riyadh.

These locations make good entry points, but they are not as good for exit

points because the Tuwayq escarpment limits your exit options.

When you construct a navigational plan, it's a good

idea to have flexibility to allow for contingencies at the end of the

trip. You don't want to make getting out of the desert into a

navigational ordeal where you must hit a specific point or your exit

strategy fails. If the only point of exit is where Wadi Birk cuts

through the escarpment, you need to

plan your exit well. If your exit point is Mecca Road, you have

hundreds of kilometers of asphalt available to complete your exit strategy. Simply

head north until you hit Mecca Road and turn right toward Riyadh.

A well constructed navigational plan means that

navigation is easy and worry free. A poorly constructed navigational

plan adds unnecessary stress and places your expedition at risk.

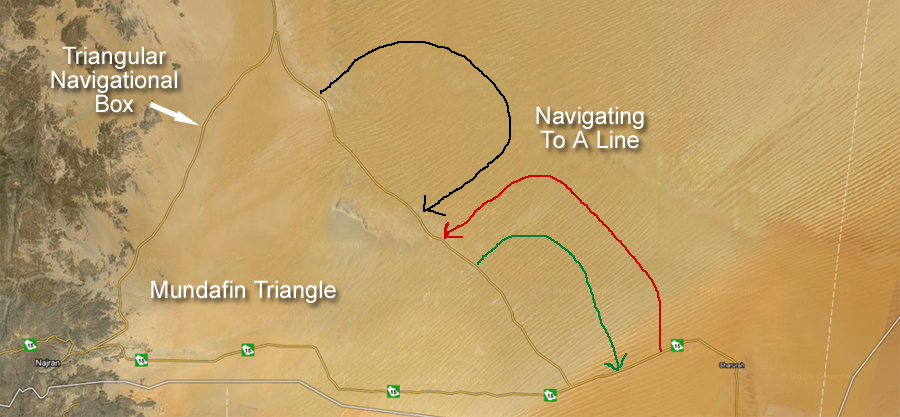

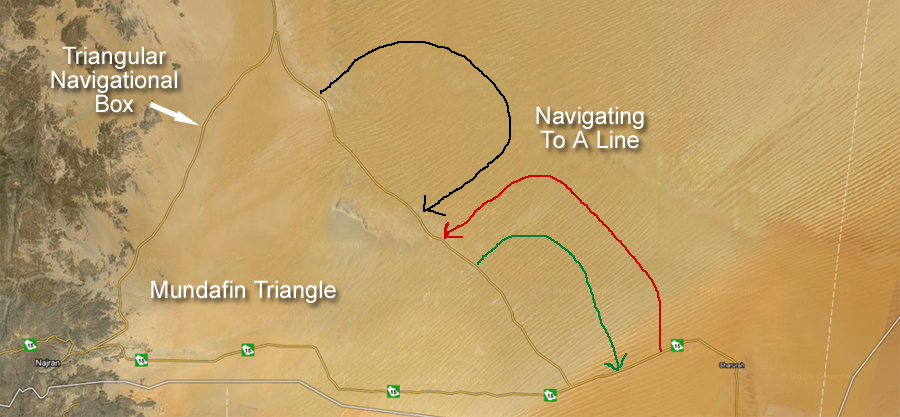

THE NAVIGATIONAL BOX

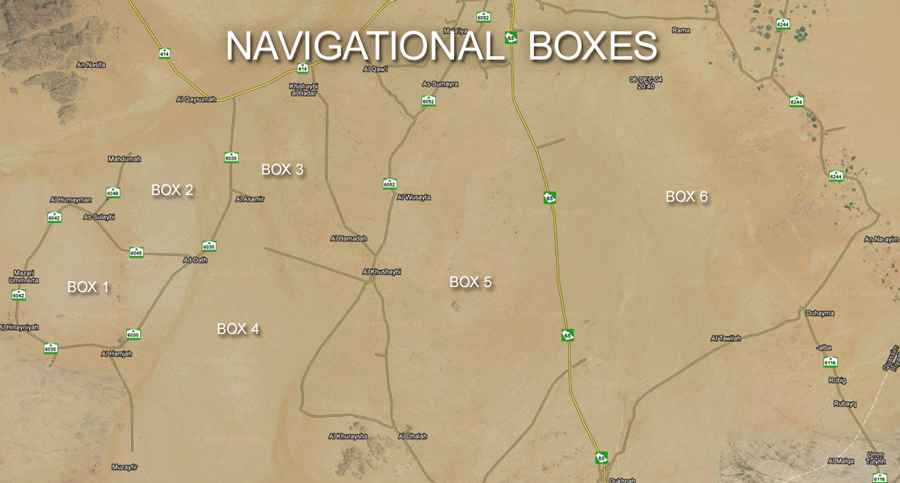

When we head out on a 200 to 400 km trip into

the desert, we construct a navigational box that encloses the area of

exploration. The edges of the navigational box are lines to which we travel

in order to

escape the navigational box.

To facilitate our exploration, we often enter a navigational box on the

largest Bedouin track we can find. That large

track transports us quickly to the area that we want to explore.

Usually desert tracks become progressively smaller as we head deeper into

the desert. Eventually the track might disappear entirely, and at that

point, we drive cross

country as we explore the countryside.

As long as there

is a track, route finding

is easy and travel is not difficult. Once we

run out of tracks, things might get challenging as the loss of the

track often means there is geographical barrier that limits how far we can

travel in a particular direction.

An escarpment or severely dissected terrain may

render travel impractical and not worth the effort because it puts the

vehicles and expedition at unnecessary risk. Breaking vehicles in deep desert is serious business. Nothing stops expeditionary travel

quite as effectively as broken

down vehicles.

When it's time to leave our navigational box, we simply select a small

Bedouin track that heads in a favorable direction. The small track

eventually leads to a larger one. Eventually we discover a

major track that takes us to one of the edges of our navigational box.

Frequently the edge of the box is an asphalt road, and once we hit the

asphalt, we say good-bye to the desert and drive the rest of the way

home on the highway.

The navigational box doesn't need to be a rectangle. Any size or shape of

box works fine. You may travel in a navigational triangle. It doesn't

matter how many sides the navigational box has. What is important is that

it has sides that you can aim for in order to get out of the desert and back to civilization.

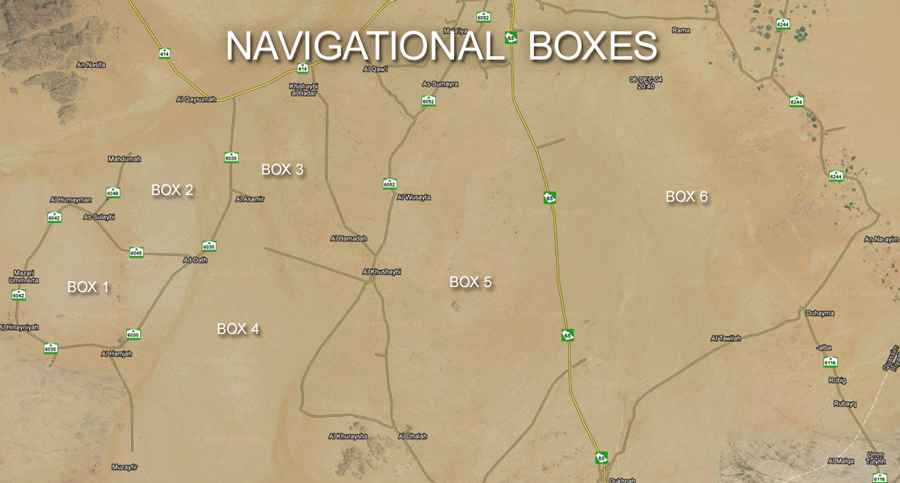

In the satellite photo, navigational boxes 1, 5, and 6 are completely

enclosed, and if you simply drive in a straight line, you will eventually

escape from the box. Boxes 2, 3, and 4 have at least one open side,

and your navigational plan should take you to one of the enclosed

sides.

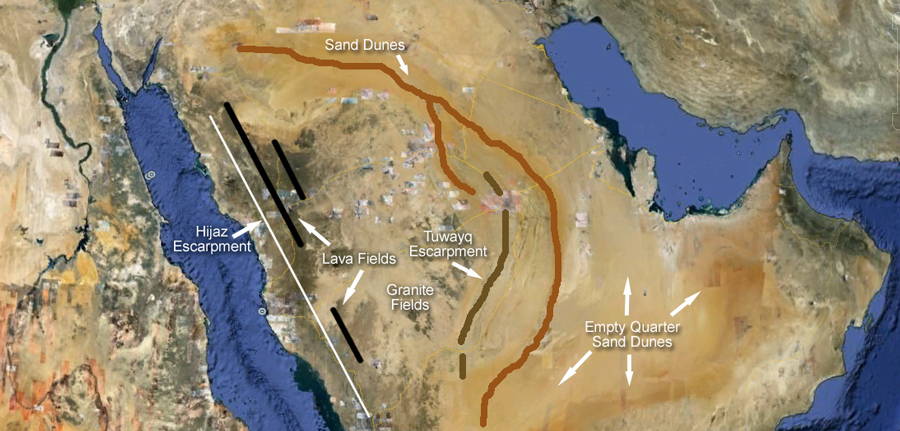

ARABIAN SHIELD

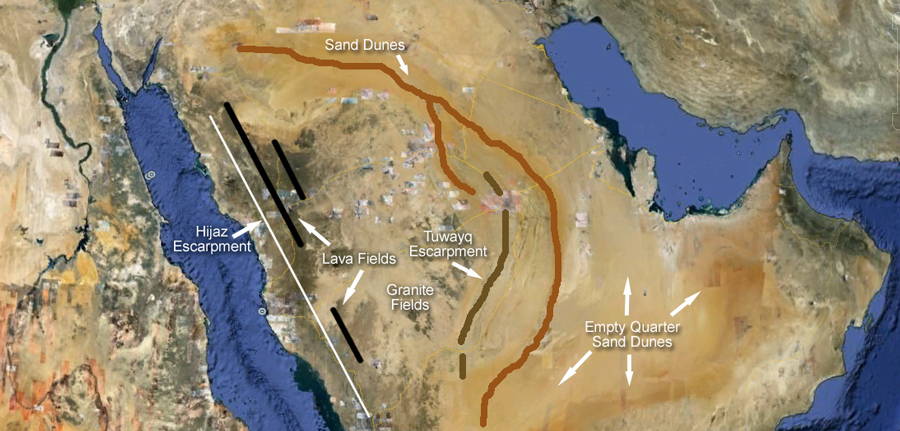

Maps often don't do a good job of representing the lay of the land.

The map of

Saudi Arabia looks flat, but nothing could be further from the truth.

The Arabian shield is elevated more than 10,000 feet in the west, tilting all

of Arabia on it's side as it gradually slopes down to sea level in the Persian Gulf. The 10,000 foot tilt creates the massive Hijaz escarpment in western Arabia, and the tilt creates escarpments and wadis

all across the country.

Tectonic plates in the Red Sea form a spreading center that continually

adds land mass to the Arabian Peninsula on the eastern side of the Red Sea

and to Egypt and Sudan on the western side of the Red Sea. As new

land forms, it elevates the western edge of the Arabian Shield

creating a massive 10,000 foot escarpment. As it pushes the land

upward, it tilts the entire Arabian shield. When you are on the top

of the Hijaz escarpment, it is effectively downhill all

the way to the Persian Gulf.

The unique geology of Arabia offers dozens of geographical regions accessible for exploration. The tilted Arabia Shield creates

wadis that run west to east until they encounter mountains and obstacles

that divert their easterly flow.

Escarpments, lava fields, and ribbons of sand tend to be oriented along a

north/south axis. Wadis on top of the shield flow west to east until

diverted by geographical barriers.

Each section of

Arabia presents unique navigational challenges that reflect differences in

regional geology. It's the geology that makes expeditions on the

Arabian peninsula so interesting. It's unrestricted access that

makes exploration so much fun.

So how do you navigate in a place like Saudi Arabia? Is it hard or

easy?

Here are the principles I have used over the years in my expeditions into

the Arabian desert.

NAVIGATIONAL PRINCIPLES THAT WORK WELL IN THE

ARABIAN DESERT

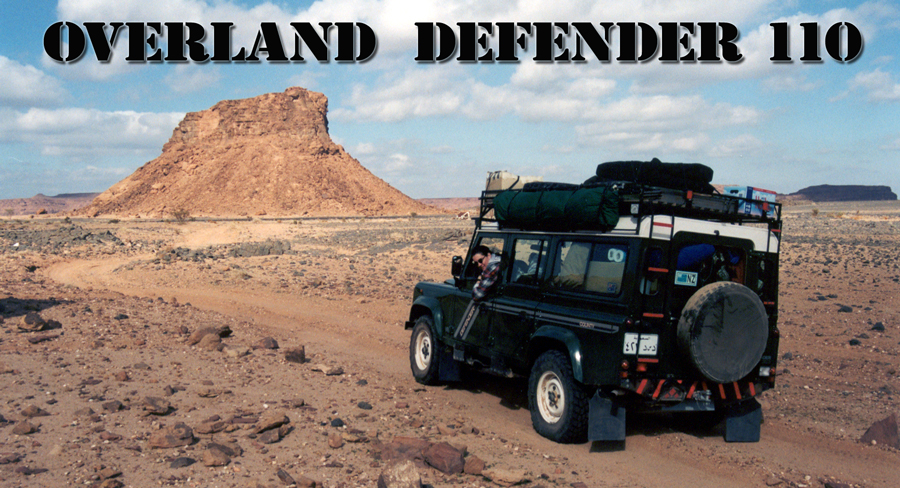

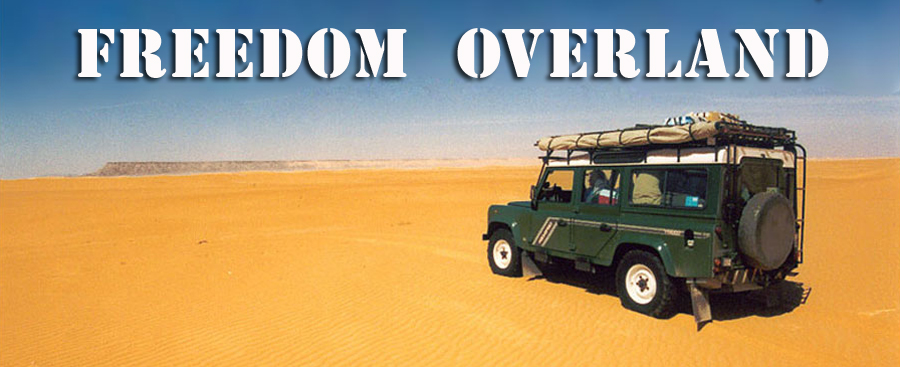

For sixteen years I lived and traveled in Saudi

Arabia. Our Defenders explored the desert from the Iraqi border to

Yemen with side trips into the Emirates and Oman. I did not always

know exactly where I was, but I always had a navigational plan to get me

where I wanted to be. Here are some navigational principles I used

for navigation in the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula.

1. Navigate

To A Line Rather Than To A Point.

2. When You Navigate To A Point, You Should Aim Off To The Right Or To The

Left Of Your Final Destination.

3. Navigate Using Bedouin Tracks When It Expedites Getting To Your

Destination.

4. Establish A Navigational Box With Sides To The Box.

5. Being Lost Has Nothing To Do With Your Location.

6. Carry Thirty Percent More Fuel Than The Calculated Amount Required By

The Navigational Plan.

I will illustrate each of these principles with stories and

photographs.

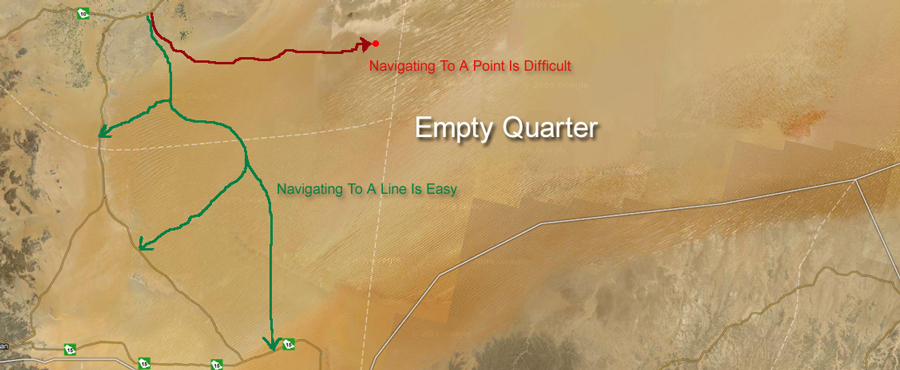

1. Navigate To A Line Rather Than To A Point.

Every time you head out into the desert, it's a good idea to set up a

navigational plan that allows you to navigate to a line.

Navigating to a point is difficult. You have a single spot on a map

that you must hit in order for your expedition to be a success. When

you navigate to a point, you are doing things the hard way. You

place yourself at a psychological disadvantage when safety and success are

contingent upon reaching a point on planet earth.

On some expeditions, navigating to a point is essential. On most of

our Arabian adventures, the real point of the trip was enjoying expeditionary travel in a

remote section of the world rather than traveling to a specific point on a

map.

As

far as I am concerned, the greatest cathedrals on planet earth are either

in the middle Pacific Ocean or in deep desert where the milky way lights

up the night sky. Billions of galaxies come into view, and you see

light that spent 4 billion years traveling through space just so it could

reach your eyes. Awesome.

The purpose of our

expeditions is adventure and awe. We avoided navigating to a point

if at all possible

Navigating to lines is supremely easy. You head out into the desert,

and when you are done, you navigate to a line that takes you home.

I am more concerned about where I exit the desert than where I enter.

I want to set up my navigational problem so that leaving the desert is a

like a walk in the park. I don't want a navigational nightmare at

the end of an expedition, and that's why I navigate to a line when it's

time to leave.

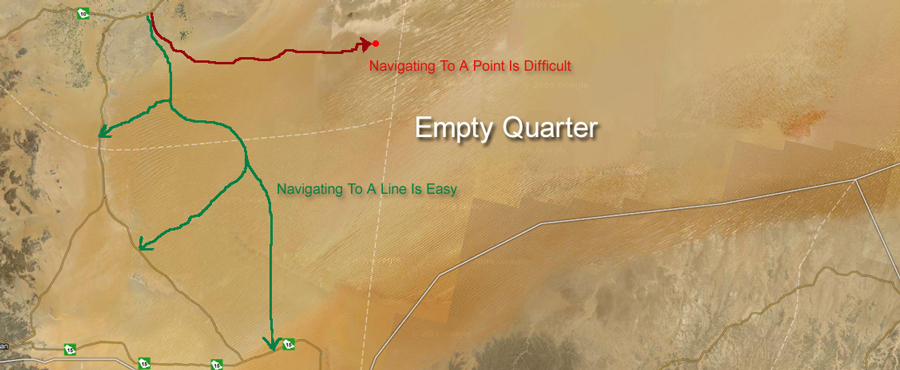

In this map of the

southwestern Empty Quarter, the green tracks navigate to a line (a road).

You start the trip by going through a cut in the Tuwayq escarpment at Wadi

Dawasir, and you head out into the dunes. You ride the giant slip

faces south as far as you want to go, and when you are done, you turn west

and navigate to a line that takes you out of the desert. The

navigational part of this trip is a no-brainer.

If you reverse the

direction of the trip, you start out at a line and travel against the

dunes trying to arrive at a point (Wadi Dawasir). This is an

extremely arduous trip because you are traveling against giant

dunes, and you are navigating to a point at the end of the journey.

You can do it if you have lots of fuel and time, but it is much more

difficult and is a bigger navigational challenge.

If you like doing

things the hard way, and if you like navigational challenges, then traveling north

is the way to go. Most people do it the easy way and travel south.

Navigational

lines can be natural or man made.

Man made navigational lines include roads, desert tracks, and power lines.

Natural navigational lines include escarpments, wadis, mountains, lava

fields, and sand dunes.

Escarpments Create Navigational Lines

The Tuwayq escarpment runs on a general north/south axis for more than

900 km in central Arabia. The Tuwayq is nearly a 1000 feet in height and

is a formidable barrier to navigation. You can drive on top of the

escarpment or at the base. There are at least eight places where

large wadis cut through the Tuwayq allowing you to get through this

geographic barrier.

In western Arabia,

the 10,000 foot Hijaz

escarpment extends the length of western Arabia with a generally

north/south orientation. Getting up and down this escarpment

generally is on paved roads. Ascents and descents typically take 45

minutes to an hour on a highway. From Jebel Sawda in southwest

Arabia, there is a gravel road that descends the escarpment for more than

ten thousand feet for those who are not faint of heart.

Wadis Create Navigational Lines

Wadis are

dried up river beds. Large wadis run for hundreds of miles on top of the

Arabian Shield. Powerful wadis several kilometers wide cut large

swaths through escarpments. Wadi Dawasir runs east for hundreds of

miles cutting through the Tuwayq escarpment and spreads out in an alluvial

fan in the Empty Quarter.

From my perch on top of the Tuwayq escarpment, I can see where wadis

dissect the countryside and eventually erode a passageway through the

escarpment. This is a place where I could navigate to a point to get

through the Tuwayq.

Wadis such as these make great places to camp. To drive in this

dissected terrain, I use the wadi for a road. Wadis contain a

mixture of sand a gravel, and they take you places that are otherwise

inaccessible. As long as it is not rainy season, wadis make

excellent roads in dissected terrain.

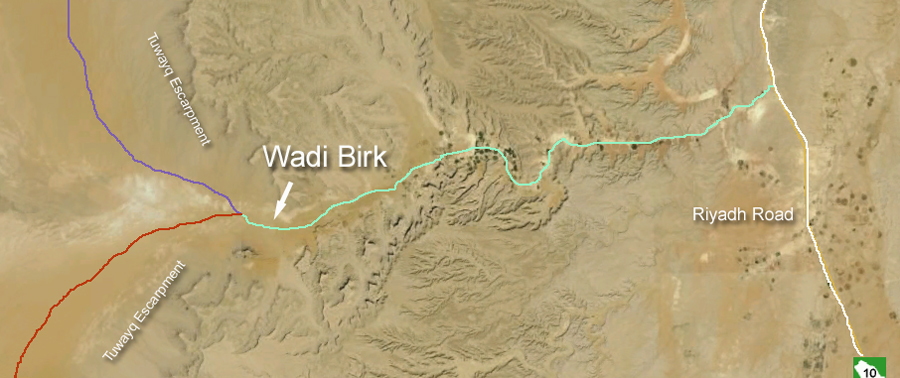

Wadi Birk has a paved road that takes you through a break in the Tuwayq

escarpment, and then dumps you in rolling sand dunes west of the Tuwayq.

This is a great jumping off point at the beginning of an expedition.

I would rather have Wadi Birk be the starting point than the ending point

of a desert adventure. I always prefer to start a trip at a point

and spend the rest of the time navigating to a line.

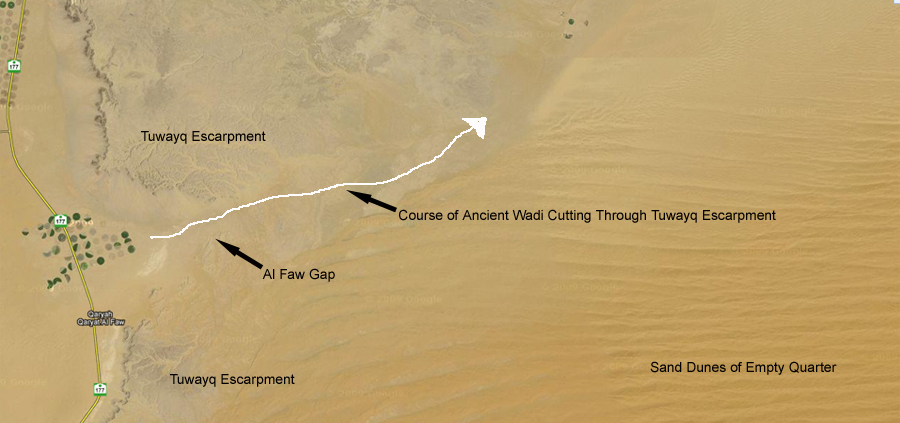

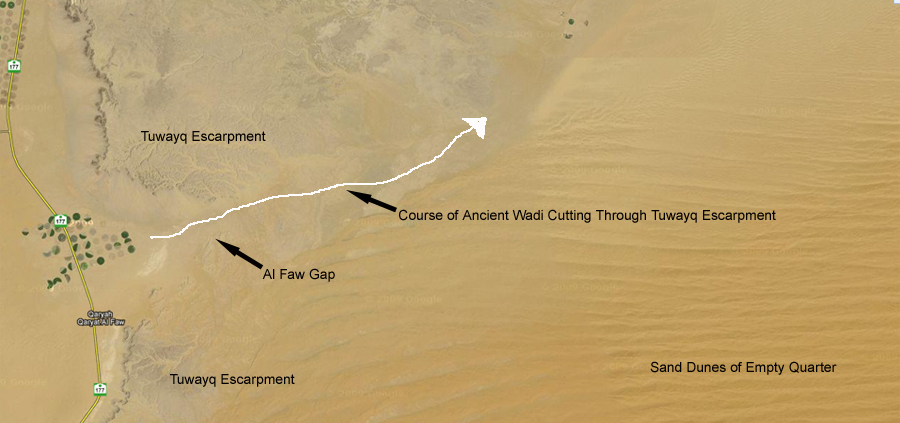

At the Al Faw gap, a large wadi cuts a kilometer wide hole in the Tuwayq

escarpment giving explorers a great entry point into the Empty Quarter.

Once again, it's better to start an adventure at a point and finish the

adventure by navigating to a line. It could be a real pain getting

back to the Al Faw gap after a week of travel in the Empty Quarter.

Sand Dunes Create Navigational Lines

Not all sand dunes are crated equal. The tilt of the Arabian Shield

and the prevailing winds have a powerful effect on the distribution of

sand on the Arabian Peninsula.

The tilt of the Arabian Shield means that all forms of erosion gradually

move sand from the elevated west to the lower elevations in the east.

Sand flows down hill.

In addition, a

high pressure area over the Arabian Peninsula creates a clockwise flow of

air that picks up sand in the north and east and deposits it in the Empty

Quarter.

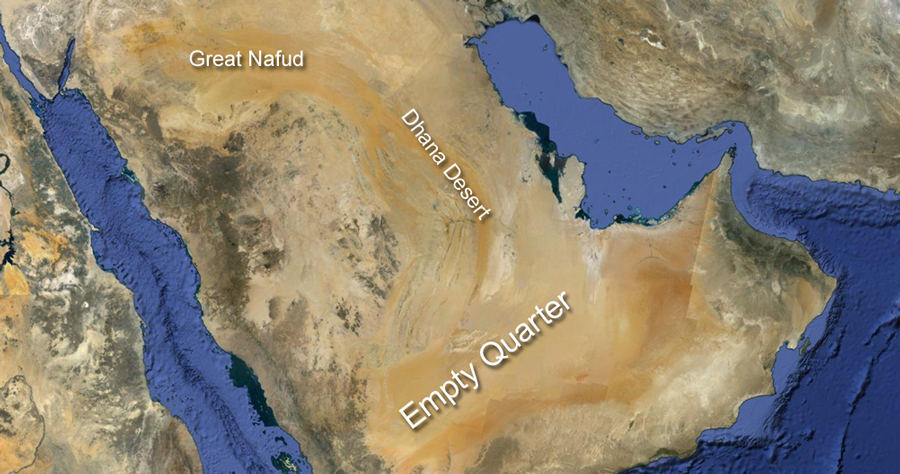

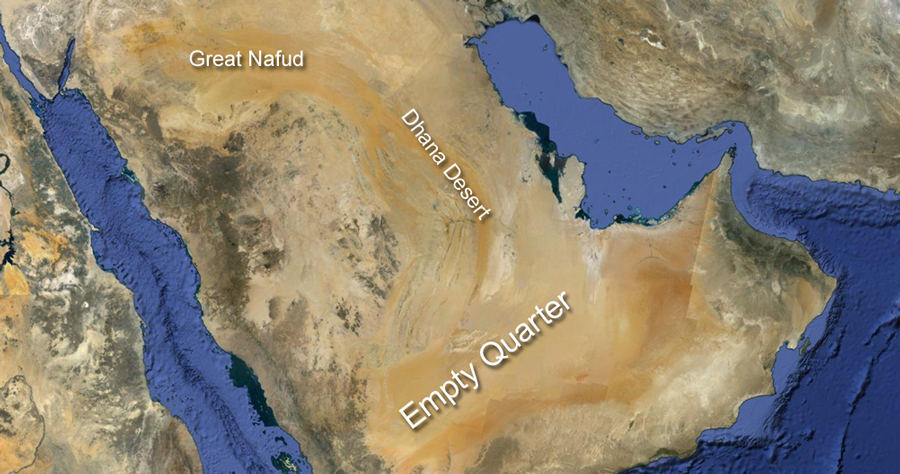

The map identifies the great named deserts (Nafuds) of Arabia. There are

many smaller named deserts that have similar orientations to the larger

ones. There are simply too many small nafuds to put on this map. If the

map appears to show sandy terrain, you can be sure there is a named nafud in

that location.

When we met

Bedouins in the Mundafin section of the Empty Quarter, they told us that

they give names to each sand dune, and they teach their children the names when

they are very young. What looks to us like just another sand dune is

a named dune to them.

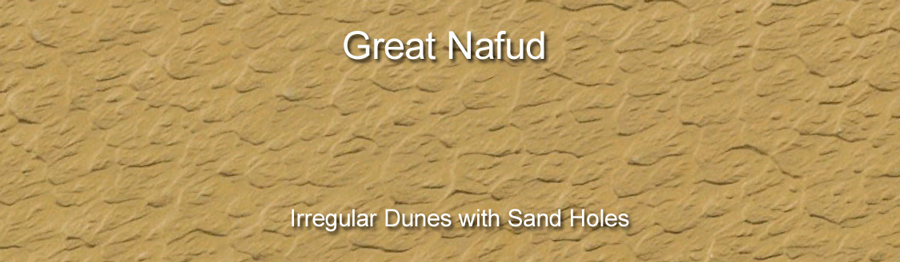

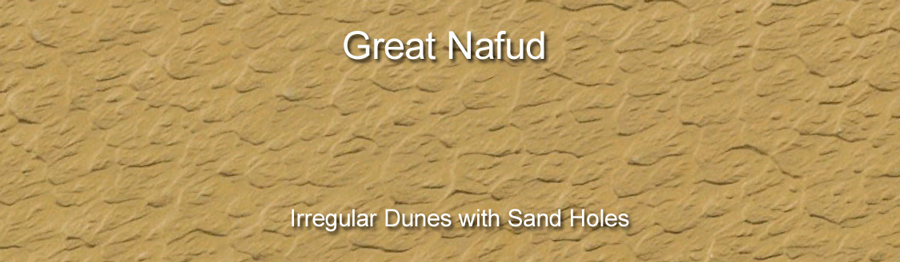

The Great Nafud is a massive sea of sand in northern Arabia.

It is

an elongated patch of sand oriented on an east/west axis. The

dunes are irregular without long corridors of sand like you see in the

Empty Quarter. Instead, each dune is a unit unto itself. In

addition, the Great Nafud has an abundance of sand holes.

Traveling in the Great Nafud presents special challenges. You can

traverse these sands if you are careful, but don't drive down into the

holes. You may not be able to drive out.

Holes are not prominent in the other major deserts of Arabia.

Occasionally holes form in other deserts, and you have to watch out for

them. No matter where you are in the dunes, you should always look

before you leap because you don't want to drive down into a hole from

which you cannot escape.

Holes can be tricky. When you look down into a hole, you see tire

tracks descending on one side of the hole and coming out on the other side.

You may falsely conclude that you can do the same thing. You give it

a go and end up bogged down to the chassis in sand at the bottom. Those tire tracks may have

been made months previously just after the rains when the sand was firm

and would support a vehicle going at a fast speed. If you try the

same thing in dry season with a fully laden expeditionary vehicle, you

become stuck in the bottom of a sand trap.

Holes have other tricks for the unwary explorer. You look at a

hole that looks navigable, but you don't pay attention to the grass

hummocks scattered on the slope of the hole. Those grass hummocks spell

disaster when you try to get out of the hole. In a

hole of the same size without any hummocks, you can get a good run up of

speed and blast your way out of the hole. But if there are lots of

grassy hummocks, it's impossible to drive in a straight line out of the

hole. You have to zig zag between the hummocks which kills your

speed and momentum, and you can't make it to the top. Your only

option is to take your shovel and remove a bunch of hummocks so you can blast out in a straight line up the side of the hole.

That's a lot of work especially when the ambient temperature is 110

degrees Fahrenheit.

I once saw a twenty foot hole swallow up an unwary Land Rover Defender .

The driver did not see the hole, and by mistake descended into the pit of

despair. The sand was extremely soft, and

to make matters worse, the hole was very small at the bottom. There

was hardly any

room to get a run up with good speed to blast out of the

sand pit. The person lowered his tire pressures as much as was safe,

and then he started driving forward and reverse until he

backed his Defender part of the way up the wall. Then he

went forward as fast as possible with a short run up and fortunately was just able

to escape from the hole.

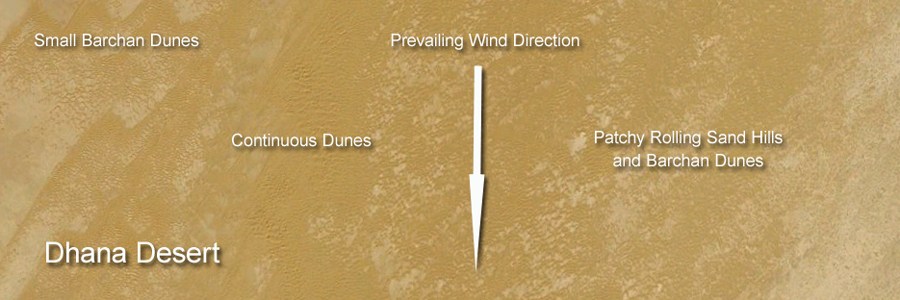

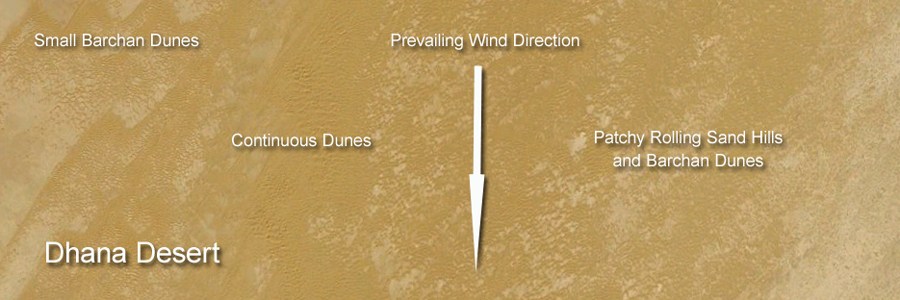

The Dhana Desert is a narrow ribbon of sand oriented on a north/south

axis, while the individual Barchan dunes have an east/west orientation.

The Dhana sands can be easy or hard depending on where you are.

Although the dunes are not tall, they can be tightly spaced. Driving

though them is a sand slalom at slow speed in which it is easy to get

stuck. The Dhana desert has something for everyone: sheet sand,

rolling hills of sand, Barchan dunes, and an occasional isolated star

dune.

You can drive east to west across the Dhana in a few hours in good areas.

You can spend days driving through the Dhana heading on a north/south axis.

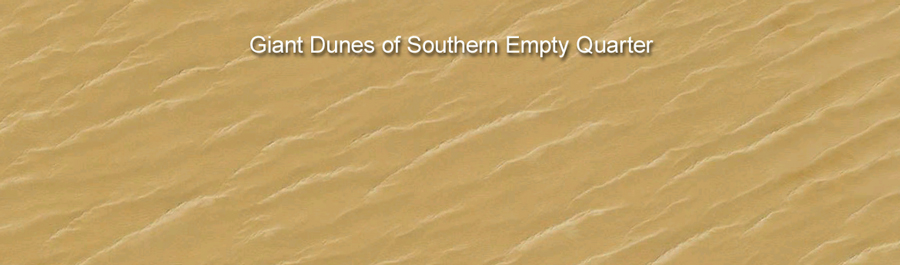

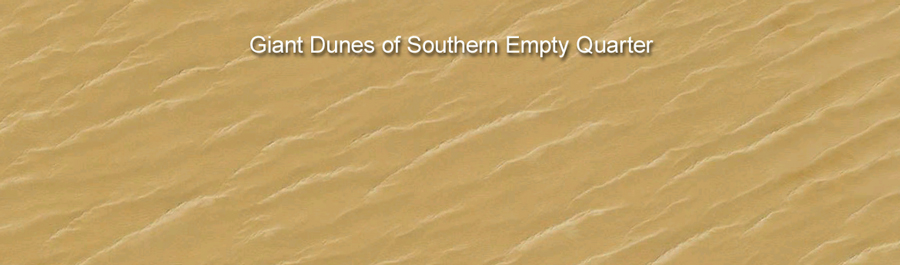

Mountainous corridors of sand dunes extend for more than a thousand

kilometers in the southern Empty Quarter. Traveling east and west in

the sandy corridors is relatively easy. Traveling north and south is

a greater challenge.

I would rather head south than north. When you

head south, you go with the slip faces. When you head in the reverse

direction, you travel against the slip faces.

Trying to ascend slip faces requires lots of fuel and hours of

persistence. You must travel in a dune corridor until you locate a

sand ramp that will get you up and over a mountain of sand.

The stacked dunes of the southern Empty Quarter illustrate how hard it is

to travel against the dunes. A single sand mountain may have 3 or 4

levels that you must ascend to make it to the top. If the sand is

soft, and if you don't have a good sand ramp on each level, you will never

make it over that line of dunes.

On

the other hand, descending down a 200 foot slip face is an exiting piece

of cake

It is impossible to ascend this slip face. A sand ramp on the right

side of the picture might get you to the top of the first level on this

giant dune in the Empty Quarter. You may have to ascend two or three

more levels before you reach the other side of the dune. Driving

against the dunes is impossible if you don't know what you are doing, and

is difficult for even the most experienced sand drivers.

Lava Fields And Volcanoes Create Navigational Lines

On top of the Hijaz escarpment in western Arabia, lava fields and

volcanoes extend in a north south line for hundreds of kilometers.

The lava fields are formidable barriers to north south navigation because

the terrain is so inhospitable. Lava eats tires, and you don't drive

though lava fields unless you are on a desert track.

Many lava fields are navigable from east to west, and if you want to make

an expedition to the lava fields, your trip will be mostly along an

east/west axis.

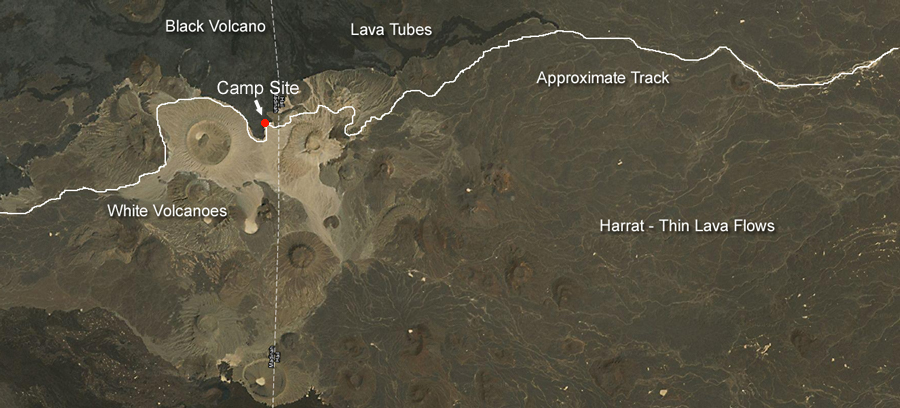

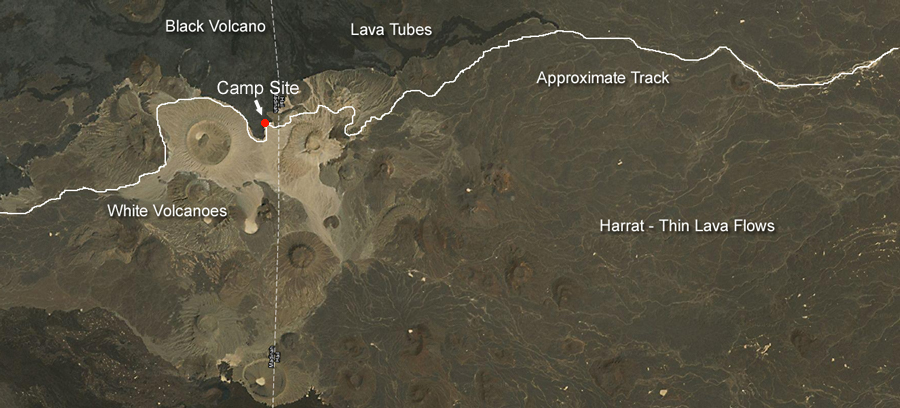

We used a navigational box when we visited the white volcanoes of western

Arabia. The eastern and western sides of the navigational box were

created by roads. As long as we followed Bedouin tracks from east to

west, we did not have a navigational problem. That's the glory of

a navigational box. Even if you don't know exactly where you are, if

you travel in a straight line on Bedouin tracks, you will make it safely

to the other side.

Until I explored the deserts of Arabia, I thought that all volcanoes and all types of

lava were black. In most places that may be true, but not in Arabia.

Get in your Land Rover and make an expedition to Jebel Beda and Jebel

Abyad - two white volcanoes in western Arabia. Jebel is the Arabic

word for mountain. Beda is the word for egg, and Abyad is the word

for white. The two white volcanoes go by the names white mountain

and egg mountain.

There wasn't much navigation to this trip. You simply drive in a

straight line to the white volcanoes and continue in a straight line until

you hit the road. Navigating to a line works great.

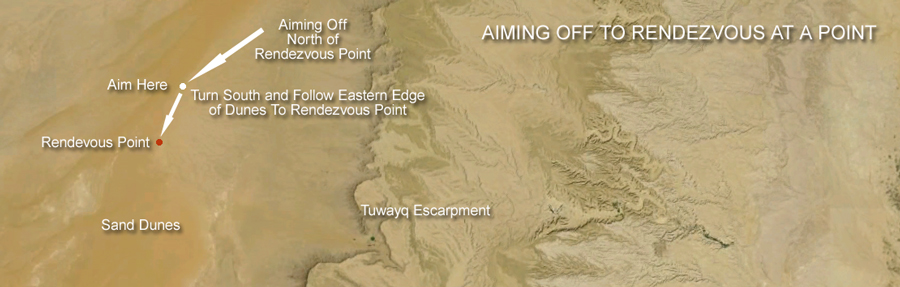

2. When You Navigate To A Point, You Should Aim Off To The Right Or To

The Left Of Your Final Destination.

Navigating to a point presents special challenges.

The basic principle is this. Avoid navigating to a point if at all

possible. The reason is simple. If you arrive

at your destination, and what you are looking for is not there, you don't

know which way to turn. Should you go right or left to get where you want

to go.

In World War II, aviators used aiming off to locate remote islands in the

Pacific Ocean. They had limited fuel to reach their destination, and

they needed to navigate in a manner that guaranteed they would not crash

because they ran out of fuel.

If they flew directly to the island, and it ended up not being where they

thought it was, they were in a dilemma. Should they turn north or

south to locate the island. They only had enough fuel to look in one

direction. If they headed the wrong way, the plane ran out of fuel,

and they had to ditch in the ocean.

They solved this problem by aiming off. They purposely navigated

their aircraft so that it would end up north of their destination.

When the navigator told them that they were on the longitude of the

island, they would turn south to arrive at the island. There was no

guessing involved as to which way to turn when they were nearly out of

fuel.

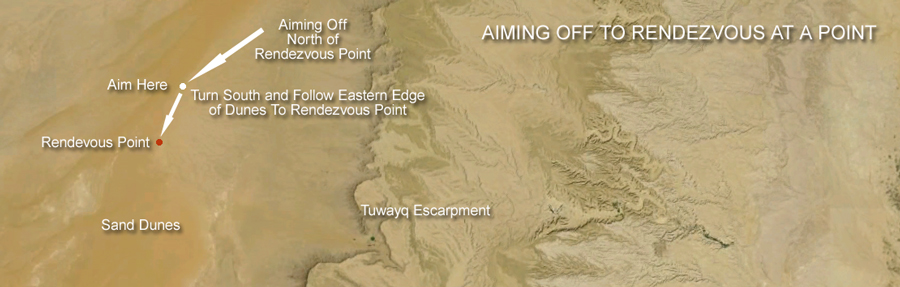

When you want to

reach a specific point, you should aim off a few miles to the right or

left of your final destination. That way you know which way to turn to get

where you want to go.

We

set up a rendezvous on the edge of a dune line with other vehicles that

had arrived earlier in the day. We came in north of their position and turned south

because we knew that they would be camping in the edge of the dunes to the

south. Because we aimed off, we knew which way to turn.

3. Navigate Using Bedouin Tracks When It Expedites Getting To Your

Destination.

All

Bedouin tracks go somewhere. Bedouins don't waste fuel driving in circles.

Every track has a purpose, and there is a good reason why it is there.

Bedouin

tracks are you best friend in deep desert. They define what is possible

and reasonable in that section of the desert.

Bedouin tracks do an exceptional job of getting you to your destination in

the easiest and quickest manner.

Shelfa is

a Bedouin gas station located 200 km into the northern Empty Quarter.

Bedouins need fuel, and all tracks in the area converge on Shelfa. Navigating to Shelfa is easy. Just

follow all the tracks.

Tire tracks endure for years in the desert. Bagnold wrote a book called the Libyan Sands

that described his adventures driving Model T cars in the Libyan and

Egyptian deserts more than eighty years ago. Travelers today can still

find some of his tire tracks in the remote desert sands and gravel plains.

Nadqan

is an

old abandoned ARAMCO outpost 100 kilometers into the Empty Quarter.

Tens of thousands of old tracks in this area converge on Nadqan.

Some of the tracks are more than fifty years old, and because they are on

gravel plain, the tracks will endure for hundreds of years.

Bedouin and ARAMCO tracks make a trip to Shelfa and Nadqan into a fairly

easy navigational exercise. If you abandon the bazillions of tracks

leading to these outposts, then navigation becomes more challenging. Route

finding is also more of a problem, because you are trying to read virgin

sand, and you don't have the luxury of following tracks that keep you out

of trouble. You get stuck more frequently when you explore in sand less

traveled. Once you leave Bedouin tracks, route

finding returns with a vengeance.

Desert tracks around escarpments will endure forever. The

track is the easiest way to get through dissected terrain. The only

change that might happen to this track is that one day it might get

converted to asphalt.

Tracks in sheet sand give you lots of latitude for creative driving and

navigation. Get on a large track and drive like a banshee, or select

a smaller track and enjoy the ride.

When large tracks converge, you need to be especially alert. You

are approaching a choke point, and a Bedouin may be coming into that choke

point at a high rate of speed from the opposite direction. The most

dangerous scenario happens when there is a choke point at the top of a

hill, and you can't see what is on the other side. The better part

of valor might be to stop your car and have a look at the top of the hill to

make sure nobody is coming from the opposite direction.

In the granite fields of central Arabia, you don't need to follow tracks

as you explore the massive batholiths erupting from the desert floor.

Thousands of square miles of sheet sand beckon you onward. It

doesn't matter if you drive north, south, east, or west. You can go

in any direction you want as long as you have plenty of fuel and a

navigational line that you drive to at the end of your trip.

Bedouins also create road signs to alert themselves and others to dangers

on the track. If you see several rows of stones piled and laid across the

road, that is a Bedouin stop sign. It means slowdown or stop because ahead

there is an obstruction or escarpment, and if you continue traveling at high speed,

something bad will happen.

Bedouin tracks are your best friend when they take you in the

right direction. Traveling on tracks protects your tires from punctures

from thorns and cuts by sharp rocks. Rapid cross country travel is hard on

tires when you are outside Bedouin tracks.

4. Establish A Navigational Box With Sides To The Box

Before you head into the desert, you create a navigational plan. If

you are lucky, you will be able to construct a navigational box that

you enter at the start of the expedition, and leave at the end. When it is time to

leave the desert, you head for the nearest side of the box. If you

can't construct a box, then the next best thing is to make a navigational

plan where you navigate to a line.

Creating navigational boxes is easy. Study your map, and it won't

be long before you have a bullet proof navigational plan.

if you enter a navigational box with enough fuel for a thousand

kilometers, you can safely navigate almost anywhere in Arabia. If

you carry a couple of thousand

dollars in spare parts and tools, you will be

unstoppable.

If you have a group of three expeditionary vehicles and plenty of fuel,

the entire Kingdom of Saudi Arabia becomes your playground.

As long as you stay away from military bases and don't go to Mecca, you

can go wherever you want. A few antiquities like Medain Saleh and Al Faw require

permission to visit, but they are few in number.

Get into a navigational box and live your sand dreams.

5. Being Lost Has Nothing To Do With Your Location.

Lost means you have run out of fuel or your vehicle has broken down, and

there is zero chance for rescue. But since you travel with at least

two other vehicles, you are not lost. Your vehicle may be lost, but

you are just fine.

The rules of engagement on Arabian highways is different than most other

countries. Two lane highways instantly become three lanes

when someone wants to pass.

The passing vehicle simply assumes the middle of the road while the

rest of the traffic moves off to the sides. This makes for exciting

travel when you are moving down the highway at sixty five miles per hour.

Your car bobs and weaves at high speed as each car asserts its claim to the

invisible third lane in the middle of the road.

Western expatriates with obsessive compulsive disorder experience anxiety

when people use the invisible third lane. They lay claim to their

patch of highway and refuse to get over in a passing situation. That

generally doesn't work well, and it could have fatal consequences. There

is an old saying, "When in Rome, pass like the Romans do."

Occasionally, things don't work out well in the invisible third lane

resulting in spectacular crashes.

This qualifies as being lost in the desert. It's crashing and

burning Arabian style.

This Series Land Rover is lost. It has been gracing the Empty

Quarter for dozens of years. If anyone tells you that aluminum does

not burn, they should check out this Land Rover.

The real risk of deep desert expeditions is not getting lost. It's running

out of fuel or rolling a vehicle with serious physical injuries to the

passengers. Self rescue is the only option in deep desert, and

you cannot afford to have a serious accident because someone will die.

In

my sixteen years in Arabia, I never heard of a single incident of a sober

person dying in the desert in an accident. The only deaths that ever

occurred were secondary to heat stroke when a person left the safety of

their vehicle and tried to walk out of the desert.

If you are ever immobilized in deep desert, you stay with your vehicle

until rescued. We always carry enough water to survive for a couple

of weeks. You should never travel in deep desert alone. The

minimum number of vehicles for deep desert exploration is three.

Having more than six or seven vehicles is a liability as long columns of

vehicles can be hard to keep together in challenging dunes and sand

storms.

6. Carry Thirty Percent More Fuel Than The Calculated Amount Required By

The Navigational Plan.

The calculation of fuel requirements for a fully laden expeditionary

vehicle is fairly easy.

A 3.9 liter V8 Defender averages 3.5 km per liter

of fuel. To decide the minimum amount of fuel to take on a trip, you use a

map measuring device to figure out the distance to be traveled on the trip.

Divide the total distance by 3.5 to figure the amount of fuel

needed. Next multiply the fuel needed by 30%, and add that

thirty percent to your fuel calculation. Using this

technique, we never ran out of fuel during our desert expeditions.

I consider fuel to be a navigational tool. If you have a surplus of

fuel, you can go wherever you want. If you have barely enough fuel

to make a trip, you have a bad navigational plan, and you need to modify

it.

Lots of fuel gives you lots of navigational options. Small amounts

of fuel give you limited navigational options. Insufficient fuel

means you are lost. Running out of fuel means you didn't have a good

navigational plan.

When I load my Defender up with 13 jerry cans, I have 1000 kilometers of

options.

We are fueling around in the Empty Quarter. Gas cans come off

the roof rack, and we top up our tanks for another day of exploration in

the desert sands.

Every now and then you get lucky in the Empty Quarter. Out of

nowhere you discover a Bedouin gas station. Entrepreneurs have taken

the tank off a fuel truck and elevated it on supports. Every couple of weeks, an enterprising tanker makes trip trip

across the desert sands, and fills up the Bedouin gas station. The

fuel truck has large tires and with skillful driving can travel to places

that are very remote.

Bedouin gas stations are few and far between.

They are true outposts in the Empty Quarter. There are no pumps to

dispense the fuel. Bedouin gas stations use gravity to fill jerry

cans.

The Sudanese expatriate filling the jerry cans most likely lives in a

small tent or under the fuel tank which functions as a tent.

WHEN YOUR GPS

BREAKS - NO PROBLEM MATES - TIME TO DO SOME REAL NAVIGATION!

1. Dead Reckoning

When all else fails, use dead reckoning to solve your navigational

problem.

Sometimes I practice navigating in the desert using only my compass.

I record compass heading and distance traveled every time

there is a significant change in course. I have found that I get a 10 km

position uncertainty for each 100 km traveled.

Zig

Zagging on desert tracks makes dead reckoning

a major challenge. Nevertheless, having an approximate position is

better than no position at all. A DR plot gives you

an approximate position that you continually refine with landmarks and

lines of position from celestial bodies.

On our desert

expeditions it usually was not that important to know our exact position because

of the way we set up our navigational box. When it was time to exit

the navigational box, the most important thing was to travel in a straight

line to reach asphalt and the road home.

A handheld compass is extremely useful when it's time to exit the

navigational box. The compass keeps you honest and makes sure that

you are traveling in a consistent direction until you hit the asphalt.

I always mount a Plastimo Iris 100 hand-held compass on my windshield in

my Defender 110. I use silicone to attach the mounting plate in the

middle of the windscreen so it is equidistant from the right and left side

of the car. I mount it slightly up from the dashboard so it is far

away from the electrical influences in the

dashboard.

As long as the air conditioning or heater fan are not running, the Iris

compass gives a good bearing check that confirms I am heading generally in

the right direction. If the exact bearing is supercritical to the success

of the expedition, I remove the compass from its mount and carry it far

away from the vehicle where I can get an accurate bearing of my track.

The compass tells me if I am heading in generally the right direction, and

it keeps me honest rather than optimistic. Often tracks slowly veer

off to the right or left, and the compass alerts you to the fact you are

no longer heading where you want to go. You need to correct your course

by selecting a different track that heads closer to the direction you want to

travel.

If you have not traveled on a track before, a hand held compass makes you

situationally aware and keeps you honest about where you are actually

heading.

2. An Aeronautical Bubble Sextant

I carried a Mark V aeronautical bubble sextant with me on some of my

trips into the desert. I was planning to sail around the world on my

sailboat, and practicing navigation in the desert was a great opportunity

to develop navigational skills. I have used my sextant more

times in the desert than I did during my eleven year sailing voyage

around the world.

The Mark V sextant uses a bubble for an artificial horizon making it

possible to take sun, moon, planet, and star sights anywhere in the world

without needing a true sea level horizon. It doesn't matter whether

you are on the top of a mountain, in a sea of sand in the Empty Quarter,

or in the middle of the Indian ocean, the Mark 5 sextant

tells you where you are within a couple of miles.

I picked up one Mark V sextant for $100 in a military surplus store in New

Zealand, and my other Mark V came from Celestaire for $600 in the USA.

They are durable sextants that are easy to use. They will tell you where

you are when the government turns off the GPS system, or if your GPS breaks or

fails due to lack of power.

I carry a small navigational calculator that has a nautical

almanac stored in memory. It also has programs for reducing star, sun,

moon, and planet sights. With a navigational calculator, it's easy to reduce an astronomical sight to a line of position, and

when multiple lines of position intersect, you have your position anywhere

on planet earth.

My bubble sextant gave me a position that was within 2

to 3 miles of my GPS position.

When I wanted to

take a sight, I steadied the bubble sextant on

my Land Rover to dampen the motion of the bubble that creates the artificial horizon.

I generally took sun sights at noon, and stars at twilight. It's traditional to take star sights at

navigational twilight when you are at sea because you need to see the

horizon when you take the sight. You bring the astronomical body down

so that it just kisses the horizon. With a bubble sextant in the

desert, you can take star sights after sunset because you don't have to

see the horizon. The bubble in the sextant creates your horizon, and

you take an evening or night site at your convenience after you have made camp and cleaned up after supper.

In practice, a twilight sight is easier because there are fewer

navigational stars in the sky which makes it much easier to identify them

when you take the sight. You get out your Simex star finder and

identify the stars, and then you take your sight. Next you turn on

your navigational calculator and reduce the sites to get your position.

A star sight with three navigational stars places you within 2 to 3

miles of your GPS position.

A sight taken of a single celestial body gives you a single line of position. Sights taken of multiple celestial bodies - 3 stars at twilight - produce

three lines of position that cross each other, and your location is

close to where the three lines of position intersect.

Single lines of position are extremely valuable when you take a sun sight

at the time of day when the bearing of the sun is aligned with the

direction of travel. In that situation, a single line of position intersects your track at

right angles,

and that intersection reveals your approximate position.

When I first started navigating in the Saudi desert, I did not realize the

value of a line of position. Overtime, I discovered that a line of

position is nearly as good as a three point fix when you are traveling in

a constrained direction. A single line of position often reveals

your location.

As you travel along the Tuwayq escarpment on

a north south axis, a single line of position from a noon site tells you

where you are. Your longitude is already known because you are

traveling beside the Tuwayq. A noon site reveals your latitude, and

tells you where you are on your journey along the Tuwayq. When you travel north to south in the Empty

Quarter, a noon site will tell you how far south you have actually

traveled, and when you need to turn right to head out of the Empty

Quarter.

Latitude

navigation is an ancient form of navigation where you head north or south

to a particular latitude, (the latitude of your destination) and then you

run along that latitude until you reach your destination. A single

line of position from a noon sight can keep you on your desired latitude,

and that may be all you need to navigate across 1000 km of desert.

Do not underestimate the value of a single line of position.

3. A Morning Or Evening Sun Sight

Morning or evening

sun sights help

determine your approximate position when you are traveling on an east west

oriented track. The trick is to take the sight when the sun is on a

bearing aligned with your direction of travel. At some time during

the morning or afternoon hours, the sun will align close enough to your

track that it will generate a useful line of position that falls across

your track giving you an approximate position. The sun works less

well at higher latitudes and works best when you are traveling in

equatorial regions. You must remember that the sun rises due east

and sets due west on only one day of the year. At other times it

will either rise north or south of due east depending on your latitude.

It will also set north or south of due west depending on latitude.

If you don't want to use the sun, you can select a

star or planet at twilight that happens to be aligned with your direction

of travel. Take your sight, and a single line of

position will cross perpendicular to your track and tell you where you are

on that track.

When you travel through the lava fields of western Arabia to visit the

white volcanoes, most of the time you travel on a east/west axis. A

simple line of position on a celestial body aligned with your direction of

travel gives you a line of position that tells you where you are on the Bedouins tracks

that traverse the lava fields.

4. When You Travel On A North/South Axis, Latitude Navigation Is A Big Help

The altitude of the north star is your approximate

latitude. The altitude of the north star at night gives you an easy

way to determine your latitude. You also don't need GMT to reduce

a north star sight.

A

noon site of the sun reveals your latitude.

A simple noon sight is an easy way to determine your position when you

travel on a track oriented in a north/south direction.

The noon site is particularly valuable because you don't need GMT to

reduce the site. Sight reduction is straightforward, and even if your

timepiece is broken, you can still get an exact latitude. You take

a noon site at the exact instant the sun is due north or due south of your

position at local apparent noon. You measure the maximum altitude of

the sun as it passes overhead. You start taking sun sights

before local apparent noon, and continue taking sights until you are well

past local apparent noon. You construct a graph that shows the

highest altitude of the sun which occurs exactly at noon. You

select the highest altitude, and reduce it to your latitude.

At local noon, the sun is due north when you are in the southern

hemisphere, and the sun is due south when you are in the northern

hemisphere. The position of the sun at local noon also lets you

orient a sun compass so you can figure out true compass directions.

5.

A Sun Compass Tells You Which Bedouin Track To Use Inside Your

Navigational Box

A sun compass tells you

whether the track you are driving on will eventually take you back to

asphalt. A quick glance at the sun shows whether you are

heading in the right direction.

There is no excuse for driving

around in circles in the desert. As

long as you use a sun compass when nothing else is available, you easily

select a track that heads in the direction you want to go. If the

track turns off in

another direction, a sun compass tells you that you are headed

the wrong way.

Navigating in the desert is similar to navigating on a yacht. You do

a lot of tacking toward your destination, and as long as pay

attention to your direction of travel, it's easy to select a track that

takes you where you want to go.

It's rare that you travel in a straight line

in the desert. Lots of zig zagging around obstacles is common.

The best you can do is to select a Bedouin track that generally heads in

the direction you want to go. Bedouins don't drive around aimlessly

in the desert because they pay for fuel the same as you.

They drive in the most direct and efficient way to reach

their destination.

Bedouins also know what is possible. They

know about obstacles, and when they drive cross country, they take detours

and obstructions into account. In a best case scenario, when it's

time to exit your navigational box, you follow small Bedouin tracks that

become larger the closer you get to the edge of your navigational box.

As long as the tracks get progressively larger, it will be easy to exit the box.

If the tracks become progressively smaller, you are heading toward

Nowhere Land, and there is a significant probability that the track will peter

out and will not take you out of your navigational box.

When you have abundant cheap fuel, exact

position is relatively unimportant except in an emergency .

Novices frequently worship at the altar of Exact Position. They feel

that if they know their exact position, somehow they are safer and better

off.

If you have a well-constructed navigational plan, most of the time your

exact position is not that important. It may be fun to plot on a

chart and make you feel good to know exactly where you are on a map, but it's common sense

and a good navigational plan that makes a trip succeed. Plotting

points on a map may tell you where you are, but they don't necessarily

show you how to get out of the desert and back to civilization. I

would rather have a well-constructed navigational plan than a bunch of waypoints

and a GPS. Ten waypoints do not constitute a

navigational plan. Too many people substitute waypoints for a

navigational plan, and when their GPS fails, they are in trouble.

When I first started doing expeditions in the desert, I was extremely

uncomfortable unless I knew my exact position on a map. Knowing my

position gave me a sense of security which was actually a false sense of

security. I thought that if I got into difficulty, I would somehow be

better off if I knew exactly where I was. In the real world of deep desert

navigation where self rescue is your only option, it doesn't matter that

much where you are. There is nobody to call to rescue you,

and nobody to notify about your predicament..

A precise position is important if you want to navigate to a specific

destination in deep desert like the Wabar Crater in the middle of the

Empty Quarter. If you have a fuel dump buried in sand, precise location is

important to retrieve your fuel. If you have to return to an abandoned

vehicle to make repairs, then precise position is supremely important. At

other times, exact position rarely matters.

I am sure some people will be uncomfortable with the imprecise way that I

navigate in the Saudi desert, and I understand why they would be

concerned. I understand why people would be critical of my approach

to navigation in the age of GPS.

I confess that I do not worship at the altar of Exact Position, and it

works for me. I always carry at least two GPS units with me on

expeditions, but I understand their limitations. I don't place my faith

in my position, and knowing where I am is little comfort if I don't have

enough fuel or spare parts to make it back to civilization.

It is rare to emerge from the desert with only fuel vapors in my gas tank

when I carry 1000 kilometers worth of fuel.

One of the reasons I carry so much fuel on expeditions is that I want to

have freedom to explore at will, and I don't want to be a slave to precise

navigation from one refueling point to the next. Navigating in the

Saudi desert with abundant cheap fuel makes exploration into a real

pleasure.

None of these principles are navigational secrets. Navigation is mostly

common sense, and constructing a navigational plan is easy and fun.

That's my navigation plan, and I'm sticking to it.

Disclaimer: I am not proposing that

the way I navigate in the Arabian

desert is appropriate in other areas of the world. Arabia is a

unique destination with relatively unrestricted access to the desert, and

what works in Arabia may not work well in other parts of the world.

I use GPS extensively when I explore off road, and nothing that I write in

this article is meant to demean or diminish the importance of GPS in

expeditionary navigation.

|