|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Minding The Gap And Connecting The Dots |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Inspiration occurs in unexpected places. As I was riding the Underground in London, I frequently heard a recording that said, "Mind the gap." The gap is the space between the train door and the station platform. When people don't mind the gap, they trip and fall as they get on and off trains. If you don't mind the gap, bad things happen. Minding the gap isn't optional if you want to live your dreams. The most important gap in our lives is the one between what we say and do. When it's all been said and done, will we have said more than we have done? The gap between what we say and do is sometimes wider than the Grand Canyon. Talk is cheap, fast, and easy. Doing is hard, expensive, and takes lots of time. The difference between saying and doing is the difference between heaven and hell, the difference between bogging down in Nowhere Land and sailing on the ocean of our dreams. We spend our lives exploring the gap between saying and doing. Some people make the gap their home and never go anywhere. Others narrow the gap and step over it making their dreams come true. If you are going to live your dreams, you will have to mind the gap between what you say and do. You will have to connect all the dots of your dreams until they actually come true. Minding the gap and connecting the dots is simply living as if your dreams are possible and working each day to make them happen. There's not much talking, and there's lots of doing when you mind the gap and connect the dots. The fastest and most certain method of

closing the gap between saying and doing is summarized in a single word:

W. H. Murray (Scottish Himalaya Expedition 1959) said it better than anyone. "Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back.. Concerning all acts of initiative and creation, there is one elementary truth the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too... Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it. Begin it now." Maxing Out Expeditions is about minding the the gap and connecting the dots of our dreams. Every day that we work on our dreams we are minding the gap and connecting the dots. Sometimes we mind the gap for years before we actually connect the dots. It required eleven years to connect the dots sailing around the world. For more than thirty years, I have been minding the gap, but I still have not connected all the dots on my driving trip around the world. For more than fifty years, I have been minding the gap and connecting the dots on positive thinking expeditions as I circumnavigate the inner world called my mind. Maxing Out Expeditions chronicles the three great expeditions of my life. 1. Sailing around the world on my catamaran Exit Only. 2. Driving around the world in Land Rover Defenders. 3. Positive Thinking Expeditions exploring the landscape of the human mind. If you are ready to close the gap between saying and doing, and if you want to connect the dots of your dreams, then Maxing Out Expeditions is a great place to start. Sailing and driving around the world are even better when you have a Positive Thinking Expedition along the way. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

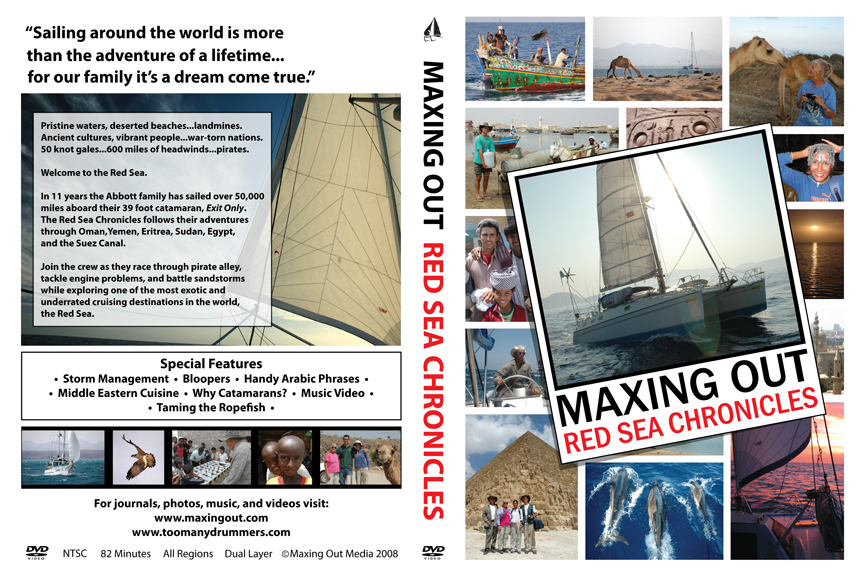

Maxing Out Circumnavigation - Captain Dave worked for eleven years in Saudi Arabia saving up Freedom Chips to finance a sailing voyage around the world. Then along came Gulf War I and the bombardment of Riyadh with scud missiles, and Dave and his family took a vacation from the war making a trip to the Miami Boat Show where they found the catamaran on which they would sail around the world. They selected a Privilege 39 catamaran that they named Exit Only, and then they embarked on an eleven year sailing voyage. Along the way they survived a global tsunami and successfully sailed through Pirate Alley and up the Red Sea in an epic voyage which they made into a movie called The Red Sea Chronicles. The aquatic circumnavigation is now complete, and Exit Only awaits another voyage to Australia after Captain Dave completes his overland expedition around the world in a Land Rover Defender. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

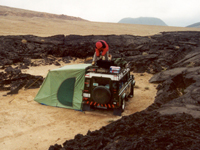

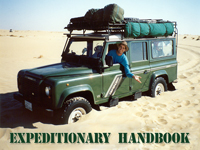

Maxing Out Overland Offroad - Team Maxing Out has been making Overland and Off-road expeditions for nearly thirty years. They started out with overland trips in East Africa, and followed that up with an expedition through Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Costa Rica, And Panama. A short stint in Liberia, West Africa was followed by a five year adventure in Puerto Rico. The Middle East beckoned and Team Maxing Out explored Saudi Arabia from the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf, and from Iraq to the border with Yemen including multiple trips across the sands of the Empty Quarter. Overland trips to Bahrain, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates came next. Our down under adventures covered New Zealand from North Cape to Inverness, and our Australian adventures included a 10,000 kilometer outback trek. We are still connecting the dots around the world, and soon we will make a driving trip around the world in a 300 tdi Land Rover Defender. We are connecting the dots in the USA before we head south around the world. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dr. Dave created the Positive Thinking Network that chronicles his Positive Thinking Expeditions. The Positive Thinking Network has more than 200 websites with a global outreach to 196 countries. Every day thousands of people join him as they explore the mountains and valleys of their mind. The last great frontier is the human mind. It's where we live, and move, and have our being. Yet, it is largely unexplored territory. The mind is a wild place, a no man's land that few master and none control. For many people, the mind is an annoying presence that intrudes into their lives and tells them things they don't want to hear. They never learn to run their mind, and the best they can do is establish a truce with the inner voice that never goes away. Dozens of Positive Thinking Expeditions on the Positive Thinking Network help you regain the high ground in the battle for a positive mind. If you want to explore your inner real estate, Positive Thinking Expeditions is a great place to start. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

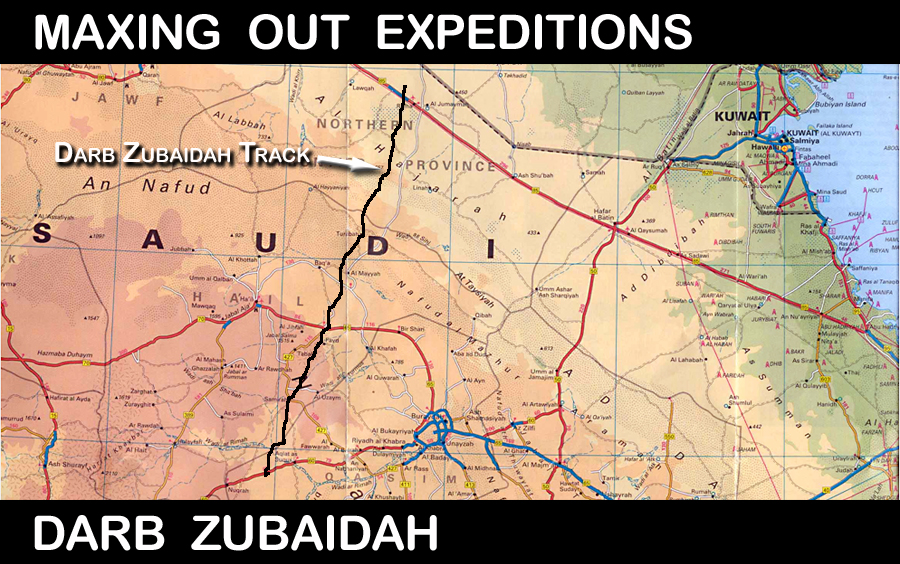

More than a thousand years ago, Queen Zubaidah from Iraq built an eighteen meter wide pilgrim road from Baghdad to Mecca. The road was called the Darb Zubaidah, and millions of pilgrims walked this road on their journey to perform Hajj in the holy city of Mecca. The trip to Mecca was arduous and fraught with danger. Pilgrims died of thirst and encountered hostile tribes during their overland trek. They paid tribute to tribes along the way in return for safe passage and fodder for their animals. It wasn't a journey for the faint of heart. Lucky pilgrims traveled in the company of military escorts, but for most it was a solitary adventure. You were on your own. There weren't any tour companies to guarantee a safe trip. We decided to follow the Darb Zubaidah from the Iraqi border to Mecca. We calculated the distance and felt we could complete the trip in a week in our Land Rover Defender 110 expeditionary vehicles. We carried enough fuel and water for the entire trip. Our Defender carried 430 liters of fuel in long range fuel tanks and thirteen jerry cans. We had two hundred liters of water and enough food to last for weeks. A trip of this nature requires at least two capable off-road vehicles to provide back up in the event of mechanical failure. I carried spare parts worth several thousand dollars - starter, water pump, belts, electronic spares, and lots of little bits and pieces. After leaving Riyadh, we spent a day driving up to the Iraqi border close to

the town of Rafha. We headed off-road just north of Rafha being

careful to not cross over the border into Iraq. Part of the adventure was using our navigational skills and common sense to follow the Darb. This was a make it up as you go exploration of the pilgrim route. It was an expedition worthy of the name. We didn't know exactly where we were going, and we didn't know what we were going to find, but we knew it would be a great adventure. Even though we didn't know the route, we had one major factor in our favor. Pilgrims on the Darb Zubaidah could only survive by following the water trail. Most of them traveled on foot, and they had to reach a source of water every couple of days, or they would die. That meant that if we followed the wadis (dried up river beds), and found the low lying area along the route, we would also discover the shallow wells and birqats that supplied water to the pilgrims. The Saudi department of antiquities placed blue signs intermittently along the route, and we often stood on our roof rack searching for blue signs with our binoculars. When we lost our way, the blue signs got us back on track. On lucky days, we actually drove down the eighteen meter wide Darb. It was awesome to actually drive on the same track that millions of pilgrims used for more than a thousand years. Part of the fun of this type of expedition is solving the navigational

problems associated with the journey. Most of the time, we followed

desert tracks or navigated cross country going from birqat to birqat.

Just because you don't know the location of the next pilgrim station or

birqat doesn't mean you are lost. It simply means you must use

your common sense and look at the lay of the land to figure out how to

proceed in order to discover the next birqat. In ten years of

camping in the Saudi desert, I have never had an intrusive visit by anyone

to our campsites. I always felt safe in the desert, and I

have been treated with courtesy and respect in all of my encounter with

Bedouins. On this particular trip, the call of nature dictated a stop near a

large convenient mound of dirt. Donna got out of the Defender 110,

and headed for the far side of the mound in search of privacy. I

glanced toward her making sure that everything was in order, and I noticed

a cobra about four feet from where she was walking. Using the loo in the presence of a cobra places you in a disadvantaged position and

is generally a bad idea. The call of nature was temporarily

suspended as I chased the cobra across the rough desert terrain. The cobra didn't want to engage us in an aggressive

manner, and it quickly slithered away as I chased it with my camera.

Within fifty feet, it disappeared down a hole into a cobra condominium.

The only thing visible in the hole was the cobra's dark eyes peering

cautiously at me. I showed the pictures of

the cobra to a colleague familiar with Arabian snakes, and he said it was a

back-fanged Arabian cobra. The moral of

the story is clear. When mother nature calls, keep an eye out for

snakes. Although they may not be aggressive by nature and present

little threat if left undisturbed, stepping on them could be a fatal

mistake. Locating the Darb wasn't that hard, but it wasn't easy either. Most of the time, we

weren't one-hundred percent sure that we were actually on the

Baghdad-Mecca road. Blue signs

from the antiquities department, reconstructed birqats, and eighteen

meter wide roads lined by rocks, confirmed we were on the right track.

When none of those things were present, we knew we were in the vicinity of

the Darb, but we might a few miles to one

side or the other of

the actual track. Our first stop on the Darb was a low lying plain pock-marked by wells. It looked like a moonscape with dozens of small craters. This would be paradise for a thirsty pilgrim. They could set up camp among the wells, and drink water to their heart's content. That many wells should cheer the heart of any pilgrim. In this field of wells, the water table comes close to the surface as evidenced by the patches of green grass scattered near the wells. Most wells had visible water six to eight feet below the lip of the well.

Queen Zubaidah constructed water reservoirs all along the road to Mecca. The Arabic word for these reservoirs is birqat, and there are dozens of them along the route. Some are in a state of disrepair from 1000 years of use and neglect. Others have been modernized with concrete and variable amounts of masonry. Birqats fill up with water during the rainy season, and hold water for many months. Most birqats have steps that lead down to the water so that pilgrims can easily draw enough water to supply their daily needs. In unrestored birqats, the remnants of rock walls suffer the ravages to time. Turrets at the corner are unique to this birqat. Perhaps they are watch towers used in the defense of the people using the water. Maybe they put lifeguards in the turrets to make sure nobody drowned in the water.

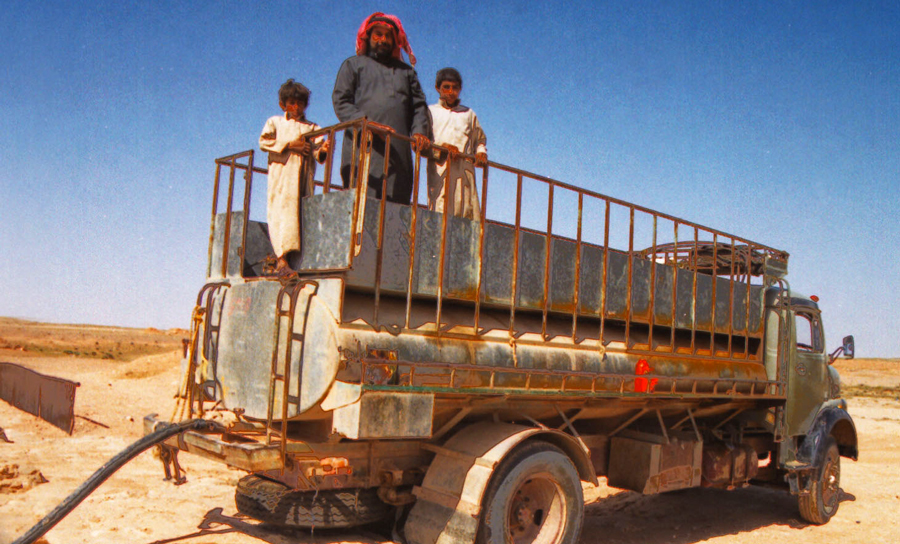

The Mercedes Benz water truck is the modern camel of the Arabian Desert. Tens of thousands of them are scattered in all regions of Saudi Arabia, and the advanced age of the truck is monumental proof of the toughness of these vehicles. They are the Timex watches of the desert. They take a licking and keep on ticking. Fully loaded water trucks drive hundreds of miles into the desert, and frequently traverse fields of sand dunes.

If a Bedouin is wealthy enough, he may actually hire a Sudanese laborer

to transport water to his camp in the

desert. Small gasoline engines drive water pumps that move water

from the birqat into the truck. Moving water isn't all work and no

play, because when you prime the water pump, you get sprayed with water

which gives you an excellent opportunity to cool off in the hot desert.

That's about the closest thing to a shower that many people ever get.

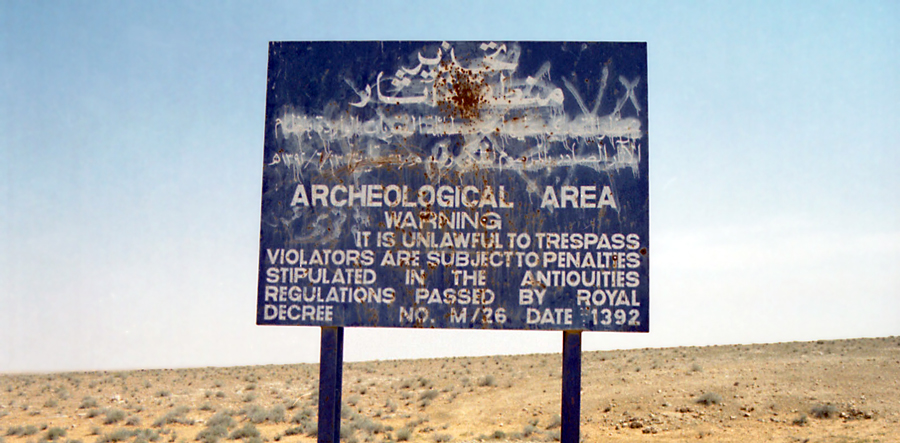

Blue signs are a great help as you drive down the Darb. They warn you to stay away from protected antiquities which keeps you out of trouble, and at the same time, they confirm that you are actually following the Darb south to Mecca. Pilgrims 1200 years ago didn't have the option of following blue signs that popped up every couple of days. Instead, they followed the eighteen meter road from well to well and birqat to birqat. Today, the sands of time have covered most of the road, and it's hard to tell if you actually are on the darb.

Shortly after setting out on the second day, we discovered an Arabian style apiary hidden in an area of bushy scrub. Beehives were lined up on a rail that elevated them off the ground. Lots of bees buzzed around us in search of nectar. Unfortunately, the nectar was in short supply.

The

bedouin solution to the nectar deficiency is to make a "nectar bucket."

They filled a large plastic bucket with sugar water as a substitute for

nectar.

Then they placed broken pieces of styrofoam in the bucket. The

floating styrofoam became a platform on

which the bees could land, and from which they could suck up the sugar

nectar and take it back to the hive. A nice piece of improvisation in

austere conditions.

Pilgrims did not have a

GPS, compass or map to guide them down the Darb Zubaidah. They

relied on God, guts, and eyeball navigation to arrive at their

destination. But that doesn't mean they were without navigational

aids. At critical places along the desert track they piled rocks to

create cairns that could be seen from a great distance off. When you

are tired, scared, and lost, a pile of rocks sends a powerful positive

message of hope and assures the pilgrims that they are heading in the

right direction.

Even today when we navigate in the desert, we record the locations of any

cairns that we encounter as they make excellent points of reference for

future journeys. Cairns are cheap to construct and when placed in a prominent location,

they serve their purpose well. Birqats eventually run out of

water during the summer heat. The Mercedes truck picks up a few gallons

of water and not much more. Dry season is setting in, there won't be water

in the birqat until rains come again. That is one long hose

reaching far out into the birqat. Bedouins like Toyota pickup trucks and Mercedes Benz water trucks. The pickup trucks do a great job of transporting family and an occasional camel or sheep. Pickup trucks are for the light lifting. Mercedes water trucks serve a dual purpose. They are both for water and for serious trekking. When it's time to move camp to a new location, the Bedouins load their tents and personal belongings onto top of the truck. They can move an entire camp in single trip if they pile their stuff high enough.

As

the seasons change, Bedouins move to new areas where there is better grazing for their

sheep and camels. In ancient times, they loaded everything on the

backs of camels to transport it to their new location. Now they load

their possessions on the back of their water truck, and the camels follow

along. On many occasions in deep desert, we had a herd

of camels chase after our Land Rover Defenders, because they thought we

might be bringing them water. Sometimes they followed us for miles

before they gave up and waited for their own water truck. This birqat is in a poor state of repair. Nevertheless, it still holds water, and there is a bedouin camp to the north in close proximity to the water. This real estate may not be Miami beach, and the water isn't turquoise, but any water is beautiful when you are in the desert. For a Bedouin with large herds, this is a great place to put up your tent and drive in your rebar tent stakes. This is truly a bedouin camp with a view. The rich green grass around the birqat will

feed many sheep and camels. The low lying land surrounding the birqat is close to the

water table, and the grass remains green far longer here than it does

in the desert a few miles away. The livestock will have many months

to enjoy the grass in this prime Bedouin real estate. The government placed iron railings around the perimeter of the birqats to prevent livestock from wandering into the water holes and to keep people from damaging the birqats by driving their off-road vehicles inside the dried up birqats when rainy season was over. Damaged birqats are far off the beaten track, and sending repair crews to fix vandalism and thoughtless damage is a major undertaking. People who damage and misuse the birqats are destroying important Middle Eastern history.

Every now and then, you discover something in deep desert that simply does not belong there. It looks like something was dropped out of a space ship in the middle of the desert, This structure qualifies as one of those mysteries right out of X-files. Hundreds of kilometers off-road

in the desert along the Darb Zubaidah

is the body of a beer truck sporting blue tarps on its sides.

The inscriptions on the body show that at one time this structure

transported and dispensed Wickuler Pilsener beer from

Germany. It is highly unlikely that any pilgrims ever drank a drop

of Pilsener. It is equally unlikely that Pilsener beer has ever been

in this area, since alcohol is forbidden inside the borders of Saudi Arabia.

When a birqat is left to it's own devices, it gradually fills with sand. If you don't clean out the sand and maintain the walls, it's not long before it disappears below the sandy desert floor, to perhaps be rediscovered a thousand years in the future. Sand storms can dump lots of sand in a birqat in a very short time. We searched for this birqat for a long time before we found it. The Birqat was difficult to locate because there was no track leading to it, and it was filled with sand. We simply drove around the countryside in a low lying area until we found it.

The mother of all

birqats is in the sand dunes on the edge of the Great Nafud. It was a major source

of water for pilgrims preparing to hike across the dunes. The

structure was easily 20 feet deep and the size of a small stadium.

If the pilgrims didn't find water in this birqat, they could at least go

down inside and use it for a soccer field.

This is your first clear view of the eighteen meter wide Darb Zubaidah. The Red Defender is driving on the Darb heading to the south. On the right side of the picture, piled up rocks demarcate the western edge of the Darb. Eighteen meters to the east, the piled rocks delineate the eastern edge of the Darb. After seeing the width of the Darb Zubaidah, you can begin to understand the importance of this road. You don't need an eighteen meter wide road to Mecca if there are just ten or twenty people passing by at a time. For that you would need a Darb that was three meters wide. But such is not the case. They built the road eighteen meters wide to accommodate the thousands of people that traveled in company on the way to Mecca. There is greater security in numbers, and historical records indicate that some bands of pilgrims with their camels traveled in groups exceeding 100,000 individuals. You need a big road to move that many people.

Today, the Darb Zubaidah passes near several small villages. These remote villages are a mixture of the old and new. In the background, on the far side of the wall, houses constructed of concrete blocks. In the middle ground, a water tank is constructed of concrete blocks and plastered on the inside to hold water. In the foreground is an old fashioned tank and storage structure constructed of mud, straw, and stones.

Old forts with large wooden doors testify to a rough and tumble existence in this ancient world. When invaders came to attack this village, people gathered inside the fort and closed the giant door. Close inspection reveals the presence of a tiny door within the larger door. This tiny door is just large enough to pass one adult person at a time. If hostile tribes attacked your village, they could only get through the door one person at a time, which was a bad idea. On the other side of the tiny door stand individuals armed with spears, arrows, swords, and knives ready to dispatch you to paradise. It's a good idea to stay away from small doors when there are lots of well-armed angry young men inside.

The

desert is not kind to traditional dwellings constructed of mud, straw and

stone. Without proper maintenance, these structures gradually is

erode and dissolve into the

countryside. The simple construction of this house is the same as

that used a thousand years ago. Mud, straw, and stone create walls, and

tree limbs create the roof

beams that they cover with palm fronds and plaster with mud.

Bedouins don't like to spend time digging sand out of wells. The simplest way to prevent a well from filling up is to cover it over with anything at hand that is free. Parts of wrecked trucks serve this purpose well. Simply drag the bed of the wrecked pick up truck over the opening of the well. Covers serve other purposes. It prevents people from falling into wells at night, and it prevents you from driving your car into the well when you navigate across the desert in the darkness. Covers also prevent thirsty animals from falling into wells. Most people shy away from drinking well water when there is a dead sheep floating in the bottom of the well.

Did you ever wonder where MacDonald's restaurants got their idea for their golden arches? Wonder no more. In the sand dunes of the Darb Zubaidah, the golden arches have been attracting pilgrims for more than a thousand years. Off in the distance, the pilgrims saw the arches, and they knew that before long, there would be plenty of water to quench their thirst, and sheep burgers would soon be on the grill. Life is good. This huge birqat is filled with sand, but you can imagine how a thousand years ago hungry travelers rejoiced when they saw the golden arches of the Darb Zubaidah.

The golden arches have

withstood the test of time. I wonder how much longer they will last.

Restoring birqats to their former glory is expensive and labor intensive. First you remove all the accumulated sand down to the underlying stone. Next, you restore the sides using flat rocks and mortar. Finally, you plaster the interior with concrete so that it will hold water. Sand is the perpetual enemy of birqats. Pilgrims must have spent thousands of hours removing sand from birqats during dry the season.

A level

plain is potentially dangerous when there are wells and sink holes around.. Drivers

who don't pay attention to their driving sometimes drive their trucks into

a well. Whole cars are sometimes swallowed up by a well or

sinkhole. This is what happens when you drive a Toyota Land Cruiser down a well. You can see how easy it would be to drive your vehicle into a well in the dark of night. Sleep walking is hazardous when camped around wells like these.

Digging a

well is easy until you reach

bedrock. After you reach bedrock, you must chisel your way down

until you reach the water table. The lower half of the well does not

require reinforcement because it passes through solid rock.

Some wells are embellished with a trough for watering animals. Draw water from the well and pour it into the plastered water trough so your sheep and camels can have a drink.

In this same field of small

wells, we discovered a giant well. You could put twenty Land

Cruisers in this well, and still it would not be full.

Near the bottom of the giant well, there is a door

with an arch and steps suggesting there used to be a tunnel that allowed

you to get down close to the water's edge to draw water. Even if

there was a tunnel, it would still be a long walk to the top with a pottery jar

full of water. Anyway you look at it, getting water from this well

is lots of work.

When Darb engineers searched for possible locations

in which to construct birqats, they

probably looked for green patches like these. A green patch in a sea

of brown sand meant that water collected there. How much water

collected would depend on the geology of surrounding terrain.

Deciding where to construct a birqat probably isn't rocket science.

If you find a green patch in a brown desert, you have discovered a good candidate.

A closer view of the smaller pool reveals where water flows into the far end of the pool on the left.

Water enters the birqat flowing down these steps into the smaller pool.

Two walls fanning out from the steps direct surface water into the smaller pool.

Although this birqat his been restored, sand

quickly fills in the reservoir transforming it into a sand storage

facility rather than a water storage structure.

Two masonry structures create arms that direct the watershed directly into the birqat.

When you don't periodically clean the sand out of a well, soon you don't have a well any longer. All that remains is the stones at the top showing the well's location. The green grass suggests that water isn't far beneath the surface. If I was in the desert dying of thirst, it wouldn't take long for me to get out my shovel and start digging.

When rain falls in the desert, grass springs up in just a few days. When the rain stops, the grass turns brown nearly as fast. Traveling in the desert after the rains is a special treat. Large expanses of desert sport a greenish mantle as grass emerges from the sandy soil. Although the desert appears parched and dead, the seeds of flowers and grass all hide below the surface ready to spring to life. You would never believe the seeds are there until you see the desert bloom with your own eyes.

The Department of Antiquities has done an excellent job of restoring and protecting the birqats and archeological sites along the Darb. I congratulate them on their outstanding efforts on a job well done. It's easy to enjoy a trip down the Darb Zubaidah while remaining clear of archeological sites.

In spite of the signs, not every respects the archeological sites along the Darb. Some people actually drive their vehicles down into the birqats. I can't imagine why anyone would want to drive in a birqat or damage it by driving on its fragile restored surface. I was disappointed to see the tire tracks in this

birqat. During our week long expedition, we never observed anyone

showing

disrespect toward the birqats or areas in which there were antiquities.

The best places to see the eighteen meter wide Darb is on sandy plains and in lava fields. In those types of terrain, rocks that are piled on either side of the Darb are proof positive that you are traveling on the pilgrim road. As you walk inside those piled up rocks, you are on the royal road to Mecca.

This blue sign identifies the location of an old mound that probably contains antiquities. We took a picture of the sign, and quickly departed the area. Traveling the Darb is a privilege granted to few, and those who travel must abide by the rules. When you travel on the Darb, you tread lightly and do not disturb antiquities.

Rocks and mortar line the bottom of this birqat. Rain water comes down the collecting channel to the right and runs into the birqat. Most birqats are covered with sand, and so you rarely see its bottom.

The magnitude of this birqat and collecting channels are apparent when you compare them to the size of the two Defender Land Rover 110s parked on the eastern edge of the birqat.

A pile of rubble is all that remains of a pilgrim station on the edge of the sand dunes. Rocks formed the foundations of buildings more than 1000 years old. Since nobody was present to maintain the integrity of the mud, straw, and rock structures, the buildings eventually melted away during rainy season until nothing was left.

This is not a pilgrim station, and it's not a Bedouin's tent. Structures such as these usually house camel and sheep herders from Sudan, Pakistan, Eritrea, and Bangladesh. I have never seen Saudis live in cobbled together shelters like this. It may not be much, but it protects you from the

cold and wind at night, and gives you privacy

as well. The satellite dish adjacent to the tent seems out of place,

and the only way for it to function is to have a portable

generator stashed away inside the tent. If you passed by at night,

you might see a camel herder watching movies on satellite

television. Pilgrims drew water from these wells for more than a thousand years. The grooves in the rocks testify to the age of the wells on the Darb. It takes hundreds of years for ropes to create the grooves in the rocks that line the mouth of the well. This was the most definitive fingerprint of the pilgrims that I encounter on the Darb.

The Darb passes through sand dunes on the edge of the Great Nafud.

Sand dunes are my favorite place to camp on planet earth, and the Great Nafud offers sand camping at its best.

If I had to give this owl a name, I would call him

"Intense". He intensely and relentlessly stared at us. Sometimes he

stood out in the open, and at other times he peeked around

bushes as if he was playing a game of hide and seek. He did not seem

interested in flying. Instead he wandered around our campsite always

staring directly at us. If there was ever a contest to see who could

stare for the longest time, the white owl would be the hands

down winner. Fayad was the only location on the Darb Zubaidah where a fence and locked gate protected the site. We drove up to the gate, and within a short time, the caretaker came with a key and showed us the foundations of ancient Fayad. Fayad was more than a town. It was also a fortress, and many

fierce battles happened in this location. Tribes made money selling

fodder and food to the pilgrims in the area around Fayad. When the

pilgrims refused to pay tribute to the tribes living in northern Arabia,

Fayad became a battlefield. Many lives were lost in the

struggle to control the pilgrim route to Mecca, and Fayad was one of the

most important battlegrounds. Volcanic mountains come into view as you head south out of Fayad. Quarries in those black mountains supplied the stone to build the town of Fayad. We wandered through the black volcanic region for nearly half a day before emerging again on a sandy plain.

Further south we discovered the granite fields of the Darb Zubaidah. Mountainous granite outcroppings rise straight out of the desert sands. How the granite got there is another Arabian Mystery that I am yet to solve. Granite batholiths make an excellent place to camp.

Red sand blows up against the granite outcroppings, and you can set up

your camp in any convenient private patch of sand. The granite

fields of central Arabia extend for hundreds of miles, and they pop up

from the desert floor in many different locations.

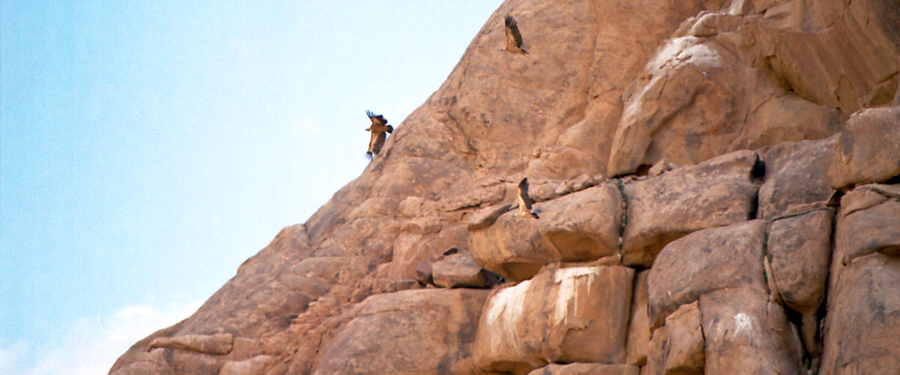

Bird droppings stain the side of this granite mountain. Egyptian vultures call this mountain home, and they also call it their out house as well. If these birds kept their poo to themselves, they would have a lot more privacy. Painting the side of a mountain with their excrement is a giant billboard advertising their presence.

We drove our Defenders right up to the granite vulture out house, and gave the Egyptian Vultures a close look. At least a dozen vultures soared above our heads, but they never showed more than a passing interest in our presence.

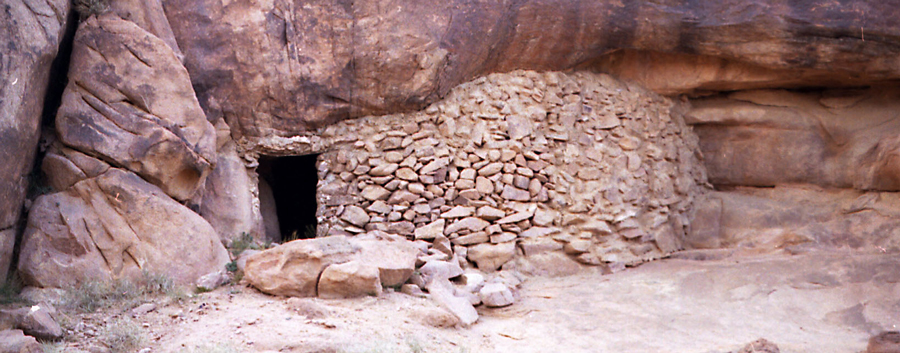

While wandering through the granite fields looking for a place to camp, we found this stone shelter tucked under a granite overhang. Although the masonry was a bit crude, and it appeared to be in a state of disrepair. it still was an impressive shelter. I would not particularly want to sleep in this cavernous space, but in a sand storm it would make a perfect refuge.

During the first three days of the trip, the skies were painted with a pastel pallet. Hardly a cloud could be found in the sky. Our night in the granite fields was completely different. Clouds were everywhere, and the sunset was brilliant gold. The sunset and clouds warned us that a weather change was about to occur. Tomorrow the weather would be different in a major way. A weather shift in the desert usually means one of two things. Either it was going to rain, or there would be massive sandstorm to make our trip down the Darb into an even greater challenge.

There is a saying, "Red sky at night, sailor's delight." Although that may be true when you are at sea, it is far from true when you are operating off road in the Saudi desert. During desert expeditionary travel, you modify the saying to, "Red sky at night, Defenders take flight." A meteorological challenge is heading your way, and you need to make preparations so that you don't get into trouble. Navigating in a sandstorm off road is a hazardous challenge.

We camped in a granite canyon tucking comfortably into

our private and

pristine granite world. Dried up wadis in the bottom of the canyon

show that flash floods rampage through canyonland during heavy rains.

The next morning, I climbed the granite boulders to photograph the sun coming up in our

campsite.

The final birqat is a marvel of common sense. The green oval in the

middle of the photo displays a birqat that receives its water from flash floods. There's not a lot of engineering going into this birqat. It's mostly common sense. You simply build a birqat at a location that takes advantage of flash flooding.

This is the partially sand filled birqat located where the wadis split.

The weather quickly changes by mid-morning. The wind is starting to blow hard, and Mark sits on top of his Defender scouting out the terrain and searching for the Darb. Off in the distance, a wall of sand is heading our way, and it won't be long before we disappear into a sandstorm. Being swallowed up by a sandstorm is not a big deal as long as you are off the road where nobody will run into you in the reduced visibility.

The wind kicks up to twenty knots with higher gusts. Mark decides to refuel before we move further into the sandstorm. We park the Defenders in close proximity. so that the green Defender shields him from the wind and sand while he pours fuel. Sand in your fuel is a good way to plug up your fuel filter and immoblize the vehicle. Pouring fuel in strong wind does not work. You don't want your precious fuel to blow onto the ground as you pour.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RED SEA CHRONICLES - DVD | RED SEA CHRONICLES PREVIEWS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||