|

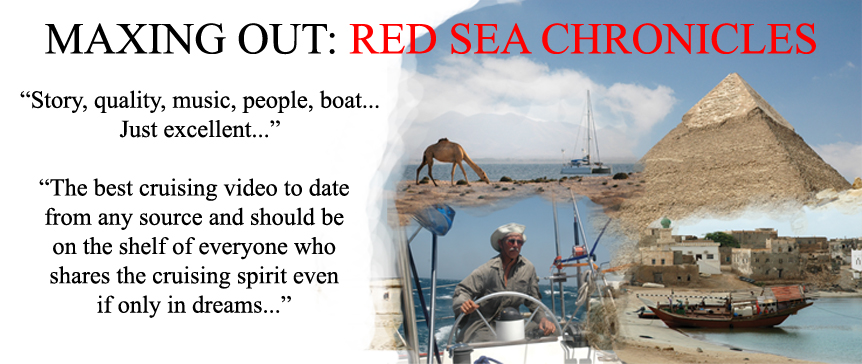

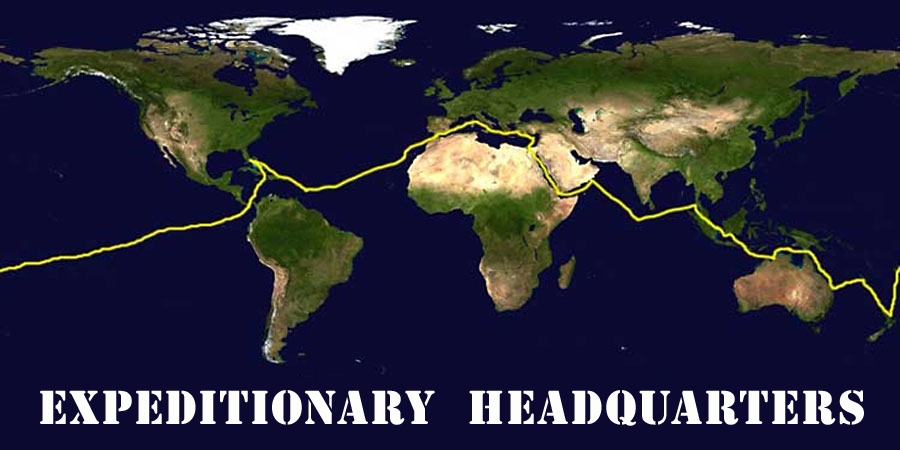

Join

Team Maxing Out

for their sailing and off-road adventures. They may be wandering, but

they are not lost. So where did they go? Some people would say

nowhere, but I would say, everywhere their heart desired. They went

everywhere they had the courage to point the bow of their sturdy

catamaran Exit Only, and everywhere they turned the wheels of their Land

Rover Defenders. They sailed more than 33,000 miles around the world on

their Privilege 39 catamaran including a trip through Pirate Alley and

up the Red Sea. Their Land Rover Defenders took them to Arabia, Oman,

United Arab Emirates, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, El

Salvador, Costa Rica, Panama, New Zealand, and Australia. Soon the

adventures will continue with a driving trip around the world and a

sailing voyage back to Australia. |

|

Discover the meaning of

Positive

Overlanding. Sand

driving teaches you about your limitations. The first lesson you learn

is that appearances are deceiving. Traversing a sea of sand may look

like a piece of cake, but fifteen seconds later you are monumentally

stuck with sand up to your chassis.You can't tell ahead of time how hard

the slogging will become until you get into gear and start moving.

Appearances truly are deceiving.The second lesson you learn is that the

only way to find out if limitations are real is to test them.If you want

to live your sand dreams, you have to test the sand all the time. You

must allow yourself the luxury of testing your limitations many times

each day. When you do that, you discover that you can do many things

you previously considered impossible. |

|

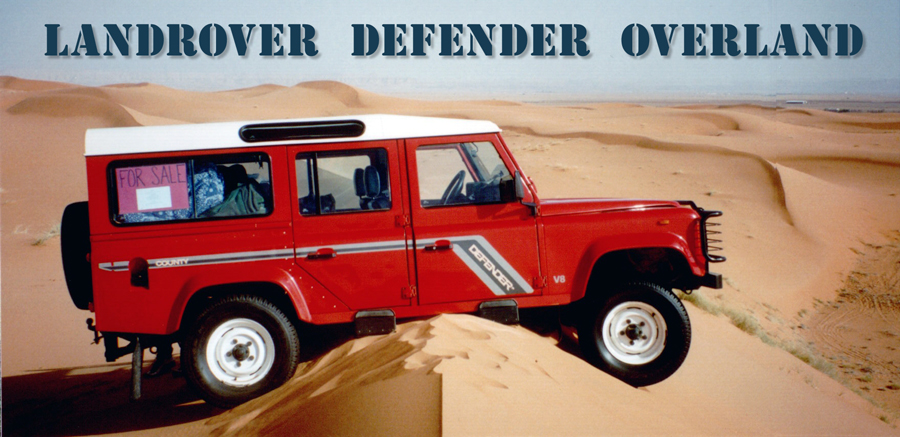

Landrover Defender Overland - When things don't work out as

planned, what should you do? Put a for sale sign of your Defender and

hope that a Bedouin with lots of cash shows up to put you out of your

misery? Sit around and feel sorry for yourself because you are

high-sided on the sand dunes of life? I don't think so. If you don't

have a snatch strap, and you are alone in the dunes, then it's time to

get out the shovel and start digging. Once the sand no longer touches

the chassis, you will be on your way. When plans don't work out, you

keep on digging, keep on fixing, keep on navigating, and keep on

driving.

|

|

Expeditionary Sandbook -

My first trip into the Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia

taught me the most important lesson of desert exploration that I ever

learned: DON'T DO STUPID THINGS! The

desert is unforgiving and doesn't treat fools lightly. Here is how I

learned that lesson.

|

|

Freedom Overland

- For

me, the dream is all about adventure, freedom, and being really alive.

Although I like seeing the sights wherever we go, I think it's the sense

of adventure coupled with the freedom to do what I want to do with my

life, seasoned with a pinch of adrenalin that makes it all worthwhile.

It doesn't matter whether I drive down a hundred foot sand dune, sail

through pirate alley, or voyage across an ocean, I still get the feeling

that I am really alive and am accomplishing something that's important

to me. I'm living my dreams, and although it's a lot of work, costs lots

of money, and spends the currency of my youth, that doesn't matter,

because I'm doing what I want to do with my life as I live without

regrets. |

|

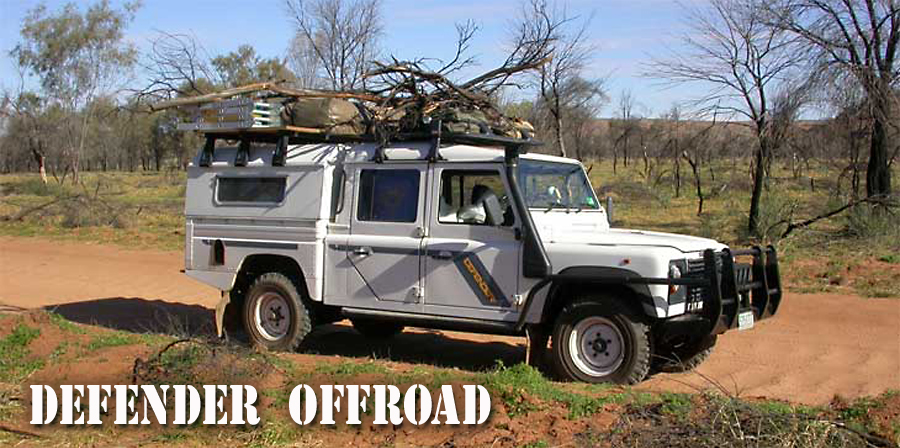

Defender Offroad

- Daydreams are

easy. Just sit back and let them happen. Daydreams are effortless

adventure. It's easy to be a legend in your own mind. Real dreams are

hard. You can't sit around making bun prints in the sands of time if

you want to make your dreams come true. Real dreams aren't a trip to

fantasy land. They are rock solid adventures purchased with blood,

sweat, and tears, and the most precious commodity of all, time. I have

always been something of a dreamer. I have gone walkabout in my mind

for thousands of hours, and that's ok, because I have spent even more

time going walkabout on planet earth.

|

|

Maxingout

Overland - Each expedition into the Arabian desert is special

for different reasons. Some trips are simply to get away from it all to

experience the solitude and stark beauty of the Arabian shield. Other

trips have a specific destination in mind, and the destination defines

the adventure. The U.S. Geological Survey worked with the Saudi

government to create a set of maps of the geology of the Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia. My favorite survey map is the Southern Nejd Quadrangle.

A smorgasbord of sand dunes, wadis, granite fields, metamorphic mountain

ranges, and archeological mysteries abound in this quadrangle. When I

think of this area, the word "awesome" comes to mind. Take a trip with

Team Maxing Out to the Tombs of Bir Zeen. |

|

Maxingout Offroad

- Travel with Team Maxing Out to the Hadida Meteor crater in the middle

of the Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia. On the trip back from Hadida, I

had my opportunity to lead the expedition into a sea of soft sand. It

was high noon, and I had no clue that in a few seconds I would be up to

my chassis in golden sand. If I had a thousand dollars for every time I

have been stuck, I would be a millionaire. I'm grateful for all the

times I've been stuck over the years. That's what happens when I live

my dreams. I've been up to my axles in sand hundreds of times. That's

terrific because it means I am living my sand dreams. I've been stuck

too many times to count, and I hope my good fortune continues. |

|

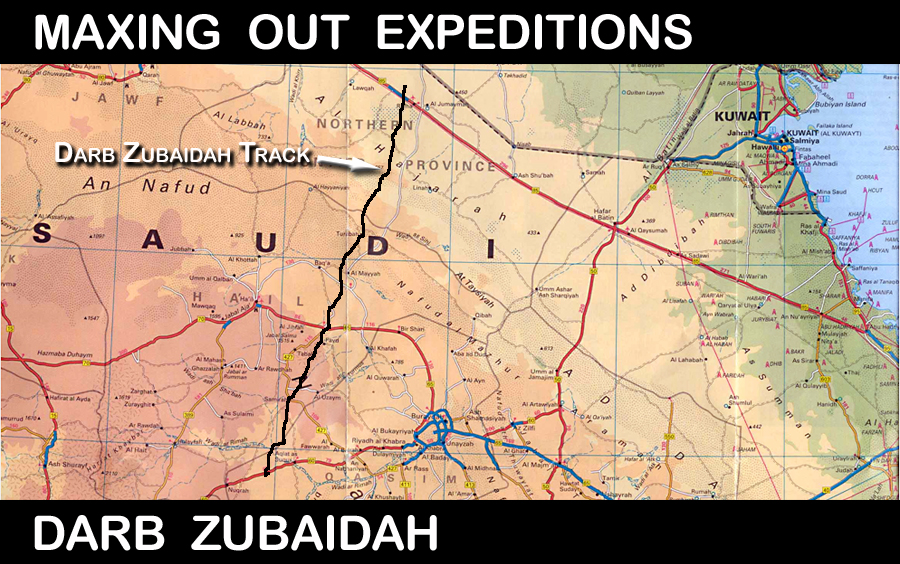

Maxingout

Expeditions - Travel with Team Maxing Out on the Darb Zubaidah

from Iraq to Mecca. More than a thousand years ago, Queen Zubaidah from

Iraq built an eighteen meter wide pilgrim road from Baghdad to Mecca.

The road was called the Darb Zubaidah, and millions of pilgrims walked

this road on their journey to perform Haj. We calculated the distance

and felt we could complete the trip in a week in our Land Rover Defender

110 expeditionary vehicles. We carried enough fuel and water for the

entire trip. Our Defender carried 430 liters of fuel in long range fuel

tanks and thirteen jerry cans. We had two hundred liters of water and

enough food to last for weeks. |

|

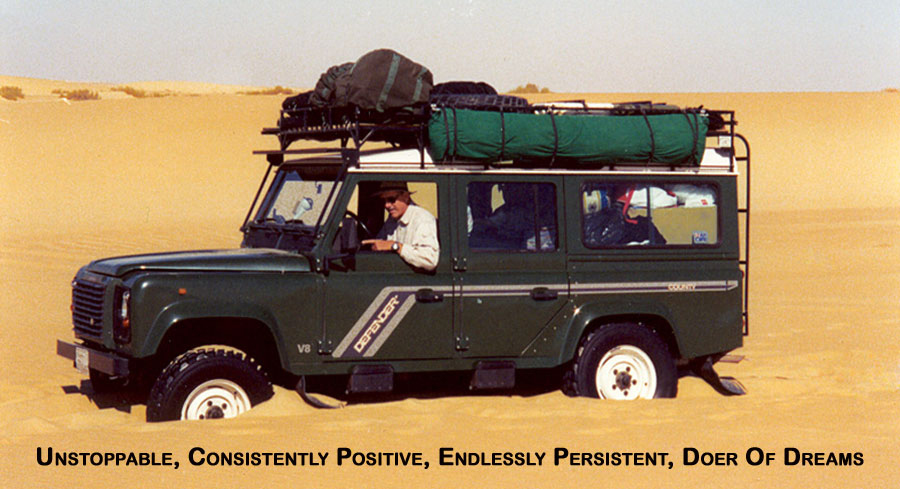

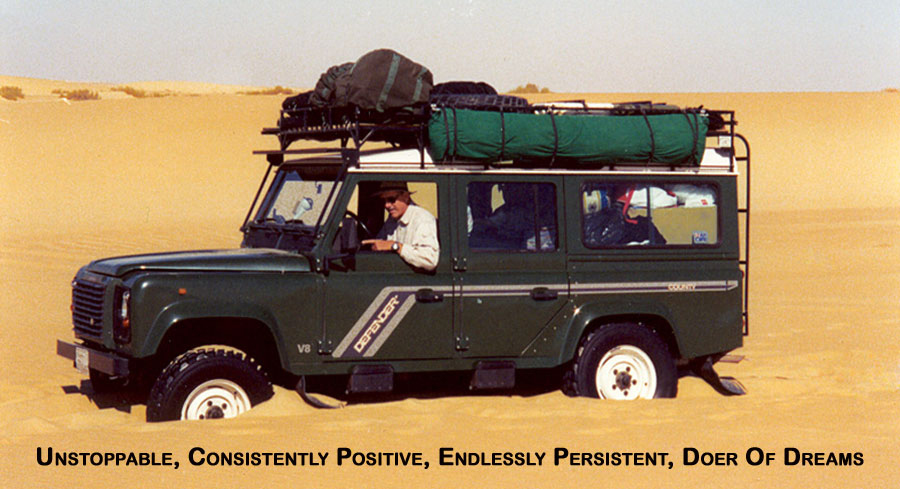

Positive Thinking Headquarters - The home of positive thinking

on the world wise web. I am grateful for all the times I have been

stuck over the years. That's what happens when I live my dreams. I've

been up to my axles in sand too many times to count, and that's terrific

because it means I am living my sand dreams. Positive Thinking

Headquarters is where you come to get unstuck. There is nothing wrong

with getting stuck as long as you don't stay there. It's time to

recover. It's time to become an Unstoppable, Consistently Positive,

Endlessly Persistent, Doer of Dreams. |

|

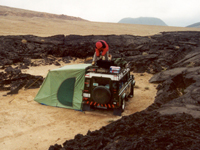

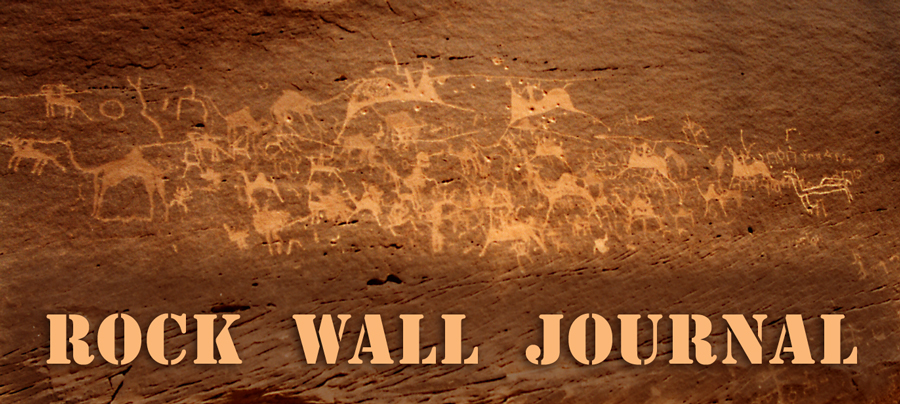

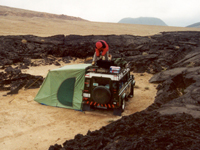

Overland

Defender 110 - Join Team Maxing Out as they make an expedition

to the white volcanoes of the Arabian shield. We decided that we wanted

to visit the white volcanoes of the Arabian shield just north of Medina.

The volcanoes are in a no man's land with lava fields stretching for

hundreds of miles. We would be foolish to make a solo trip to this area

in the heat of summer. But if it's the cold month of December, if we

have two spare tires and enough water to survive for a couple of weeks,

and if we are willing to burn one of our spare tires to make a smoke

signal in an emergency, then a solo trip is not crazy. |

|

Expeditionary Handbook - Let Team Maxing Out show you the art

and science of expeditionary navigation in the Arabian Desert. Not all

expeditionary navigational problems are created equal, and your approach

to navigation varies with terrain, capability of the vehicle, and degree

of access to the land. Limited access makes navigation more

challenging, and unlimited access gives you hundreds of options when you

plan your expedition. Situational awareness forms the foundation of

successful expeditionary travel. Situational awareness means that you

know yourself, your vehicles, and the desert in which you travel. You

must know your vehicle well and understand its capabilities and

limitations. |

|

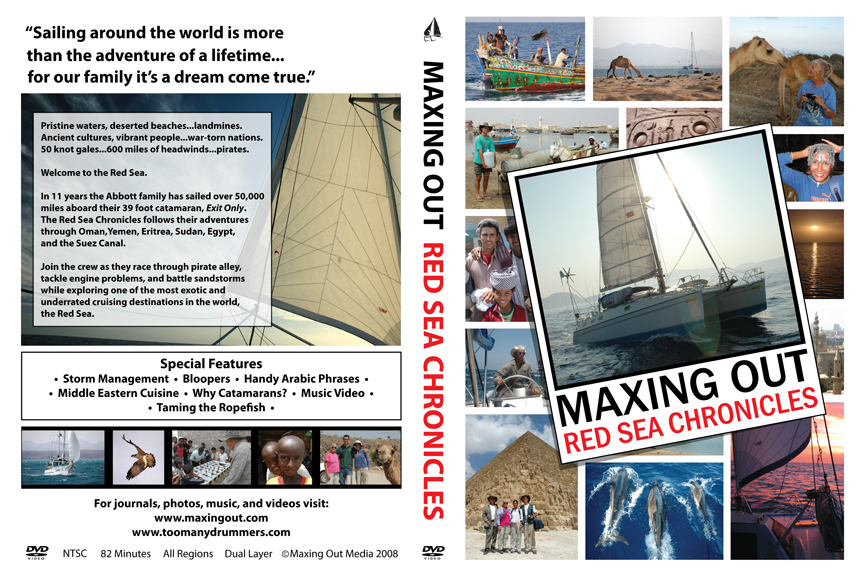

Rock Wall Journal - Team Maxing Out conquers a sand ramp in the

Empty Quarter of Saudi Arabia and then studies the petroglyphs of the

Rock Wall Journal. The ancient people who created the Rock Wall Journal

were not simple-minded cavemen waiting to evolve into real human

beings. These highly intelligent people had an appreciation for the

natural world in which they were immersed. They displayed their focus

on the natural world with stylized drawings that are still pleasing to

modern eyes. Although they had a limited palate and only a few tools

with which to work, they created unforgettable panels of rock art. |

|

Arno's Wall - Everything Including the Kitchen Sink - Winton, Queensland

Ozzie Outback Murals - Life Before Cell Phones, Texting, and Twitter |

|

Follow

Expeditionary Headquarters on Facebook |

|

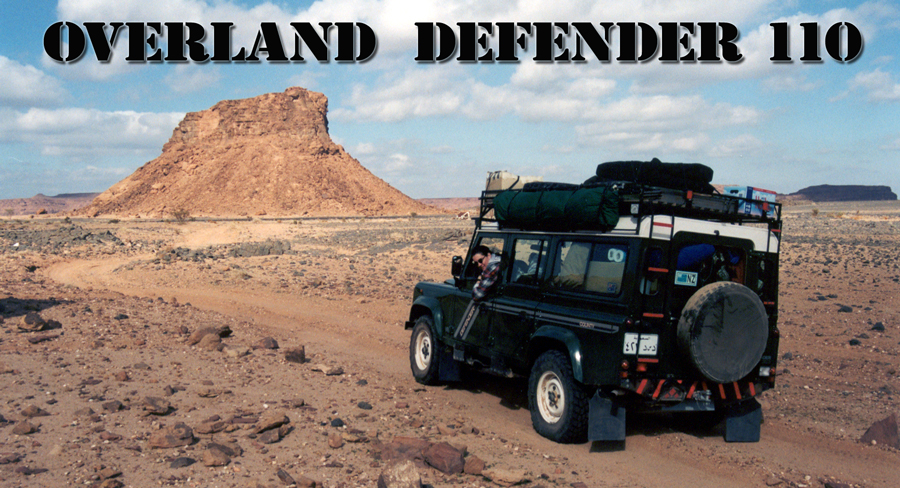

We always traveled in a Defender 110 when journeying in the Empty Quarter.

During my sixteen years in Arabia, I owned three different Defenders, and

all of them did deep desert exploration.

Green Defender cruises the desert sands on Michelin XS sand tires at about

18 psi inflation. Examination of the pictures show the ballooning of

the tires giving excellent floatation in a loaded vehicle heading out for

a week in the sand dunes.When I first started

driving in sand, I tried driving at 25 psi, and I frequently bogged down

and had to recover the vehicle with sand ladders, winch, or tow strap.

Once I dropped the tire pressure down to 16-18 psi, I rarely got stuck.

At those tire pressures I have never broken the bead and slipped a tire on

the rim. I don't use any bead lockers.

We carry Arb air compressors to reinflate the tires

up to 35 psi when returning to the asphalt.

Green Defender has an awning on the right side of the vehicle, and a tent

mounted on the left side. The full length roof rack carries fuel,

food, firewood, sand ladders, and assorted camping gear.

This is my third Defender 110 with a 3.9 liter V8 gas engine.

This sand machine will take you anywhere you want to go in the Empty

Quarter as long as you have enough fuel. The V8 engine is amazing.

As long as you are in gear and have the engine under load, you can push

the accelerator all the way to the floor in first or second gear without

worrying about blowing the engine. It's not very fuel efficient, but

you can nearly always blast through soft patches of sand if you are in the

correct gear, and you have the accelerator all the way to the floor.

I have never heard of anyone blowing their engines while working at

maximum RPMs in the dunes.

This is the roof of Green Defender. The Brownchurch style roof rack

carries eight jerry cans of fuel with jumper bars holding the jerry cans

in place. The back of the roof rack has a mount for sand ladders and

a high lift jack. The roof rack also carries boxes of water, boxes

of firewood and a second spare tire.

On the left side of the roof rack is an awning with poles, and on the

right side is a tent mounted to the vehicle.

On deep desert expeditions, we carry 13 jerry cans of fuel. Eight of

the jerry cans lay flat on the roof rack, and five reside in a purpose

made box in the back of the vehicle. In addition, we have an

auxiliary long range tank in the right rear wing that empties directly

into the main 80 liter tank. When fully fueled, we carry 430 liters

of fuel for deep desert exploration.

We calculate fuel requirements in the following manner. Using a map

measuring device, we trace our route on the map so that we accurately know

the number of kilometers involved. From experience, we know that our

Defenders get about 3.5 kilometers per liter on average in the sand.

We divide the measured distance for the expedition by 3.5 to figure the

amount of fuel needed, and then we add another 30 percent to compensate

for all the zig zagging in the dunes. Using this technique, we

usually come out of the desert with one jerry can still containing fuel at

the end of the trip. We have never run out of fuel on a deep desert

expedition.

This trip has three vehicles. Two Defender 110s, and one Toyota Land

Cruiser. The Land Cruiser is running a 4.5 liter engine, and the two

Defenders have 3.9 liter V8s. All the vehicles have plenty of power

to deal with heavy loads and soft sand. The White Defender and Land

Cruiser have one advantage over the Green Defender. Both have

Shaheen sand tires designed for conditions just like this. Shaheen

sand tires have excellent flotation, and sometimes they float over the

dunes while my Michelin XS tires sink into soft sand.

When I first started driving in sand, I thought that wider tires might be

better in the dunes. It turned out that wider street tires did not

work better. They tended to act more like a sand plow and provided

less flotation. In really soft sand, they pushed sand in front of

the tire piling it up especially at slower speeds.

Shaheen sand tires have zero tread. They are like aircraft tires,

and they tend to hydroplane on wet streets. You must be very careful

driving on Shaheen tires on asphalt after a rain shower. You may

slide around like you are driving on ice.

People who spend lots of time in the sand frequently have two sets of

tires for their Defenders. One set is for driving on the streets

around town. The second set goes on just before you go on a trip in

the dunes.

Our first camp on this expedition is in the small dunes of the northern

Empty Quarter. In this area, the dunes are like small rolling hills

of sand. You drive up one side of the dune and down the other side

without encountering a slip face. The dunes are tall enough that you

cannot see what's on the other side, but you can drive on them at a good

speed because you know there isn't a slip face on the other side.

The terrain is flat sandy plain with rolling hills of sand. When

it's time to camp at night, you pick a flat location that has firm ground

so that your Defender doesn't bog down at your chosen campsite.

Camping in the dunes is generally safe as long as you observe a few

important points.

Don't camp too close to the last sand dune that you

crossed before you set up camp. The reason is straightforward.

When Bedouins drive in the desert, they often follow the tracks of

vehicles that are ahead of them. This makes it much easier to read

the sand, If the tracks are solid, and if they don't sink into the

sand, then route finding in the dunes is much easier. You find a set

of tracks heading toward your destination, and you follow them. If

the tracks show that the leading vehicle bogged down, the following

vehicles diverge off the track so they also don't get stuck. If the

track looks good, they continue driving with much greater freedom and

speed.

Bedouins often drive in the desert at night when it's cooler. If

they like your track and follow it, you may have a rude awakening in the

middle of the night when they pop over the dune and into your camp.

Most likely it will scare both them and you. No harm is done as long as

you are not parked immediately on the far side of the dune.

On this particular campsite, that is exactly what happened. My

daughter wanted to camp at the base of the dune in the direction from

which we just came. She wanted to tuck her sleeping bag in the

danger zone. I told her that it was too dangerous, and she relented.

In the middle of the night, a truck came over the dunes and would have run

over her if she has been in that location.

We parked the Defender so that it protected everyone sleeping in our two

tents. That way if someone came barreling though at night, they might hit

our Defender, but they would not run over us as we slept. I probably

should have had put my Defender farther away from the dune to reduce the

risk to the Defender.

The other two vehicles camped further out on the sandy plain, and there

was no danger of being run down in the night by anyone unless they were

intoxicated or blind. Examination of the white shelter between the

two vehicles shows that the wind is blowing hard in this section of the

northern Empty Quarter.

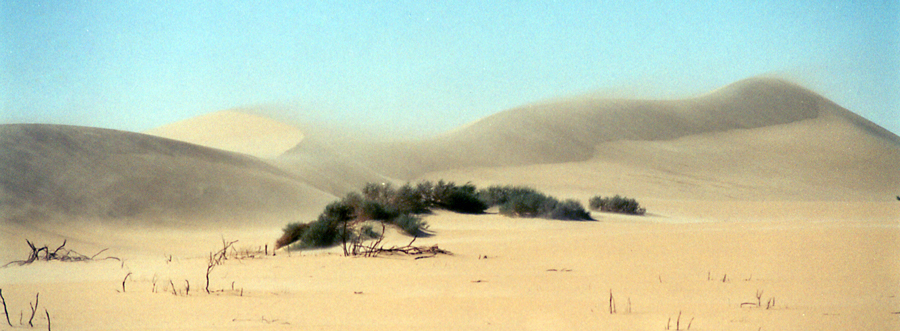

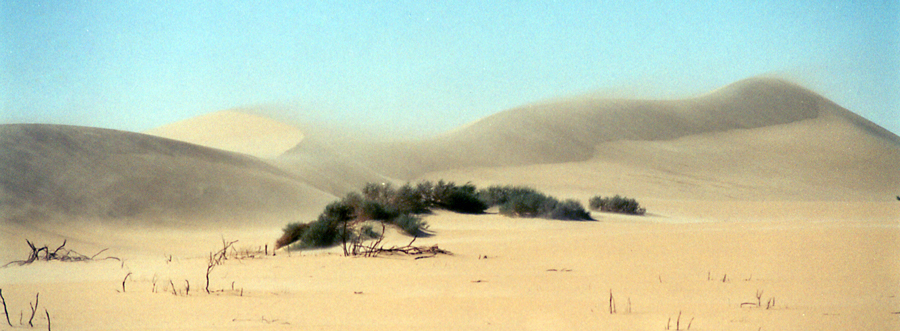

After traveling 200 kilometers south, the sandy plains and rolling dunes

disappear. Barchan dunes surround us on all sides, and as we journey

south, we slide down hundreds of slip faces as we traverse row after row

of dunes.

Because the prevailing winds are out of the north,

the barchan dune lines are oriented east to west. A single row of

dunes can extend for hundreds of kilometers in the southern Empty Quarter.

Once the Barchan dunes begin in earnest, you cannot drive around them.

It's over the top and down the slip face as you head to the center of the

Empty Quarter. Heading south is the easy direction of travel.

When you turn around and go back the other way, you spend lots of fuel and

time searching for sand ramps that will allow you to ascend the dunes to

get around all the slip faces that dominate the countryside.

When wind blows strong out of the north, the sand

flies in sheets off the tops of the dunes. If you get downwind of

these dunes, you better put on your sand goggles, or you will get a ton of

sand in your eyes.

The blowing sand deposited on the downwind side of the dunes takes a long

time to compact into firm sand. It frequently is powder soft, and if

you attempt to drive there, you may sink up to your chassis. You

wouldn't want to drive or camp there because blowing sand gets into

everything and camping is miserable.

Sometimes you get stuck at the bottom of a slip face because you are going

too slow as you descend, and when you hit the bottom, a soft sand trap

awaits. This tends to be a greater problem in larger dunes than

smaller ones. As you come slowly down the side of a slip face, it's

a good idea to accelerate near to the bottom just in case you are entering

a sea of soft sand. A heavy foot on the accelerator may allow you to

power through the sand trap and move forward far enough to get on firm

ground.

Bushes and obstacles on the far side of a slip face can be a nasty

surprise. You pop over the top of the dune, and foliage at the

bottom blocks your way at the base of the dune. That is a great

formula for getting stuck at the bottom, and it will be a major exercise

in vehicle recovery because maneuvering options are limited.

Calculating your fuel requirements must take into consideration that

traveling in the dunes is a two way street. You probably are going

to return home in approximately the same direction from which you came.

Going against the dunes requires more fuel than going with the dunes.

When you go south with the dunes all you need to do is ride down the slip

faces and enjoy the trip. There will be soft patches here and there

that will stop you in your tracks for a short time, but at least you are

not traveling against slip faces. Going against the dunes requires

more fuel and route finding is a bigger challenge. You can't travel

in a straight line. You spend time traveling in the valleys between

the dunes looking for sand ramps that will get you over the slip faces.

Sometimes, you may need to drive ten kilometers before you can find a sand

ramp that will get you over a particularly large dune with a giant slip

face.

The left side of this picture has several sand ramps that are good

candidates for getting you up and over the dune line.

Going against the dunes gets more complicated when dunes are stacked on

one other in two or three levels. In this situation, you find a sand

ramp that gets you over the first row of dunes, and then you drive on the

higher level looking for a second sand ramp that will put you over the

second row.

Sometimes there is no way over the second or third level, and you have to

descend back down from whence you came. Then you travel parallel to the

dunes once again until you find another sand ramp and attempt to go up and

over, and hopefully around the slip faces that block your way home.

Reading the sand is difficult. The lead vehicle that does route

finding is the one that gets stuck most frequently. It's simply a

fact of life when you drive in sand. There is simply no way of

knowing that sand will be soft by just looking at it.

If it is important that we don't get stuck for some strategic reason, then

the best way to find out if the sand is soft is to get out of the truck

and walk in front of the vehicle. You walk to the right, left, and

straight ahead.

If you are lucky, firm sand may be two feet in front of your truck.

Sometimes, if you turn left you will be on terra firma in ten feet.

But when you walk in front of your truck, and there is nothing but soft

sand for hundreds of feet, the smart thing to do is to come out backwards.

It's faster and less exhausting on people doing vehicle recovery.

If the ambient temperature is 100 degrees, it's not safe to use sand

ladders and push by hand when vehicle recovery requires an hour of hard

work. Someone will get heatstroke at worst, and everyone will end up

dehydrated at best.

The Land Cruiser determined that it was impossible to move forward to firm

ground, and the quickest and easiest way to recover this vehicle is to use

a winch. In a few minutes of winching, the expedition is once again

on the way to the meteor crater.

Later in the day, shadows grow longer and sand takes on a darker

appearance. Depending where you are in the Empty Quarter, sand

varies from a reddish color to a pale tan, and everything in between.

Getting between the slip faces in this picture would be easy as there is a

well-developed sand ramp between the two slip faces. It doesn't get

any better than that when you want to travel against the dunes.

As you travel south, rows of dunes often spread out. You may have

two or three closely spaced rows, and then you have rolling hills of

beautiful sand for a kilometer or more before you come to the next row of

well-developed dunes. In the valleys between the dunes, the sand

tends to be firm, and it's pure joy to glide over the sand. The tire

tracks to the right show that the sand is relatively firm. When I

drive over sand like this it reminds me of sailing over ocean swells in

the Pacific Ocean, and the best thing is that the sand swells don't move.

It's late afternoon, and shadows grow long as the golden hour approaches.

Sand takes on a golden hue, and life is good. Tire tracks in the

foreground reveal the presence of exceptionally firm sand.

Why does this campsite have a circle of tire tracks all around?

We commonly make such a circle when choosing our camp just to be certain

that we aren't setting up a camp in soft sand. If we bog down when

we drive in a circle, we move to a different location.

Ending the day by bogging a vehicle in a campsite is a poor way to finish

an expedition in the dunes. Equally, waiting until morning to

extract a bogged vehicle is not the best way to start a day.

Hence, we drive around our campsite to test the sand

before we choose our final resting place for the night.

Reading the sand is most difficult at high noon. Shadows from the

morning are gone, and intense sunlight directly overhead reduces contrast

to such a low level that it's easy to make serious mistakes. Without

the contrast, you may drive off a small slip face without realizing it's

there until your car suddenly drops three feet - a very rude awakening.

The opposite can occur. You may not see a two foot sand ridge

in front of you until your vehicle hits it and pops violently up over the

elevated sand ridge. Mistakes like that place great strains on your

suspension and frazzle your nerves. One of my friends drove his

Defender off a small slip face that he did not see, and flexing of the

vehicle's chassis resulted in a permanent wrinkle in the skin of his

Defender next to his left rear tail light. Hogging of the frame can

put creases in the sheet metal.

I have seen Defenders pop over a ridge of sand that they did not see, and

suddenly the vehicle starts making a horrible grinding noise.

When the Defender went over the sand bump too fast, it broke one of the

engine mounts. Now when they step on their accelerator, the engine

twists slightly in the engine bay, and the fan rubs on the fan shroud

making a horrible noise.

When I was learning to drive in sand, my instructor showed me how to bump

my Defender over a three to four foot slip face (from the wrong side of

the slip face). If you drive up to it at just the right speed, your

Defender will bounce up and over the slip face. It's a great

technique when it works, but it's also the recipe for breaking an engine

mount. If you are going to do stuff like that, you better carry

spare engine mounts when you are traveling in deep desert.

Although there isn't much contrast in these dunes, you have one important

factor in your favor. Wheel tracks ahead of you reveal a safe path

through the dunes. By looking at the tire tracks, you can see where

the sand is firm and where it is soft, so you know when you need to step

on the accelerator. When the going gets tough, and there is no

contrast in the sand, we always look for tire tracks to make our journey

easier.

In the foreground just beyond the ripples in the sand, a light colored

band goes from one edge of the picture to the other. This light

golden band is one of those tricky sand surfaces that can fool you as you

approach it in conditions of low contrast. The golden band may be a

three foot high wall of sand that you may pop over and in the process

break an engine mount. That same surface may have a gentle slope and

not be a problem. Sometimes you have to stop your truck a distance

off to discover what's happening so you don't make a serious mistake in

deep desert.

This line of closely spaced dunes is very tough to navigate at high noon.

You don't want to drive fast because low contrast makes it easy to to have

a problem. At the same time, the dunes are closely spaced with an

irregular pattern of sand hills. In this location, winds alternate

between two different directions. The dominant wind pattern is from

the north causing the longitudinal rows of dunes. But in between the

longitudinal dunes are secondary dunes created by winds from the east.

The jumble of east/west dunes mixed in with north/south dunes means tough

going, especially at high noon when there is little contrast.

I would avoid the dunes in the distance and make my best efforts to escape

this mess by traveling right to left in the foreground where there are

some barely perceptible tire tracks on the left side of the picture.

Low contrast means drive with care. Whether you are heading north or

south, it appears that these two lines of dunes terminate about a

kilometer in the distance. In this case the better part of valor is

to make an end run around the dunes rather than try to go over them in

conditions of low contrast.

Contrast is relative low, but a passage through the dunes looks within the

realm of possibility. The dunes are closely spaced, and if the sand

is soft, you are in trouble. Trucks will bog down. If the sand

between the dunes is firm, you will breeze though wondering what everyone

was worried about.

Driving down a slip face is true joy. The sand on this slip face is

relatively firm as the Defender isn't sinking down to the chassis as

frequently happens on large slip faces.

Red Land Cruiser is gutting it out driving through soft sand on Shaheen

sand tires. I have seen him drive out of a bogging situation like

this by lowering tire pressure down to 8 psi, and then putting the vehicle

in lowest gear and slowly creeping forward or back. You can quickly

tell whether you can creep out of a sand bogging by watching the vehicle

and tires. If the vehicle moves forward or back a tiny bit at a

time, the technique may work. If the tires simply spin and the

vehicle sinks down further, then it's useless to continue spinning the

tires. It will only make things worse.

If you have sand tires and you are willing to lower your pressure down to

8 psi, you can sometimes drive out of a serious bogging.

When I first drove in the Empty Quarter, I coined a new saying, "SASTRUGI

HAPPENS".

Sastrugi are the wavy elevated ridges of sand created by blowing sand.

Sastrugi comes in two types. There is hard sastrugi and soft

sastrugi.

Sastrugi happens in the valleys between the dunes. Hard sastrugi is

very hard, and feels like driving over giant corrugations or speed bumps.

It will shake your vehicle until you wonder if something is going to

break. It will shake your teeth until they rattle.

Soft sastrugi is soft like quicksand. It looks

like you are going to be hammered by severe corrugations as you approach a

patch of sastrugi, but the instant you enter it, you immediately sink up

to your chassis in soft sand.

You can't tell ahead of time whether the sastrugi is going to be of the

hard or soft variety. You simply must drive though it to find out

what is going to happen.

If you think the sastrugi is soft, you step on the gas and try to blast

through it. If it turns out that the sastrugi was actually hard and

you are going too fast, the sastrugi will shake your vehicle to bits, and

unsecured gear will be flying around in your truck by the time you reach

the other side.

If you think the sastrugi is hard, you let up on the accelerator and slow

down so it won't shake everything up. If it turns out that the

sastrugi is actually soft, you instantly bog down in the soft sand.

Some days you feel like you can't win.

When you encounter sastrugi, you have several options. You can drive

around it like a skier doing the giant slalom. You can stop your

truck before you get to the sastrugi and walk through it to see whether it

is hard or soft. You can hang back and let someone else drive though

it. You instantly discover whether it is hard or soft when you look

at his tire tracks. If it is soft, you put your foot down and blast

through. If it is hard sastrugi, you drive though at a slow and

gentle pace.

In late afternoon, the dunes look like King Midas reached down and turned

the dunes to pure gold. This is the stuff from which sand dreams are

made. Every time I set up my camp in the golden dunes, I feel like I

won the lottery of life, and this is my prize. I could come back to

these dunes a thousand times and never tire of them.

We like to arrive at camp by 4 p.m. so there's plenty of daylight to set

up camp and cook our supper before dark. In the late afternoon, we

have a chat about possible places to set up our tents. It's not hard

to find a place in a million square miles of sand. The only decision is

whether you want to camp high or camp low.

The people on this expedition generally prefer to camp high so they have a

tent with a view. Other's prefer to camp low where it's harder to be

discovered by passing vehicles.

During daylight hours, you are never aware of other vehicles in the

Empty Quarter. But at night the desert comes alive. You

sit around the campfire or lie on your cot listening to vehicles far off

in the distance. If you pop your head out of the tent, you see the

loom of headlights bobbing in the night sky as Bedouins drive at night in

the dunes.

In the daytime far off the beaten path, you feel like you are exploring an

isolated solitary world. At night you realize you are never alone.

I wonder where we should go next? Hmm. I

know. We'll just follow these tire tracks and discover the

Wabar meteor crater in the center of the Empty Quarter.

Welcome to the Wabar Meteor Crater, also known as Hadida.

The Wabar meteor broke up into multiple fragments before it struck the

dunes. It's unclear how many craters are present at Wabar, and we

will probably never know. That type of research takes lots of money

to answer questions that only a few people are asking. Some craters are

obvious, and others have filled in with sand in the past four hundred

years. Lots of sand gets moved around in the Empty Quarter in 400

years.

When the meteor struck the dunes, it ejected tons of superheated debris in

concentric rings around the impact site. It looks like the remnants

of a giant campfire in which the sand caught fire leaving charred remains.

Donna stands on the sloping side of a meteor impact site. At the

present time the hole is no more than 50 feet deep compared to the present

height of surrounding dunes. One wall of the impact site is

relatively vertical, and the other side slopes gently downward and is

covered with melted and compressed sand.

The color of the debris varies significantly from location to location.

Some areas have mostly white debris, and in other areas the debris is

mostly black.

This debris ejected from the impact site gives a clue to the location of

the meteor strike. Since the force of the meteor hitting the earth was the

equivalent to that of a thirteen kiloton bomb, it surely must have created

a deep hole. One the other hand, scientists believe the meteor came

in at a very low angle, and that may limit the size and depth of the

original crater. According to excavations in 1932, the largest

crater was12 meters deep.

Debris consists of white impactite (a sandstone like rock formed from

compressed heated sand), and black glass formed from melted sand.

The impactite appears white through and through, and you can see the

striations where layers of sand were compacted together. The black

glass rock was molten, and it takes different forms. I contains bits

of impactite, and fragments of the iron and nickel meteor.

The laminated compressed structure of white impactite is clear. It

is lightweight and feels like piece of white cinder.

Melted superheated sand formed the black glass seen all over the site.

Some of the smaller pieces of black glass look like black tear drops.

Some have an obsidian-like appearance but without conchoidal fractures

seen in obsidian. Melted black sand incorporates white pieces of

impactite and rusty meteor fragments. This specimen of black glass

has two spots of rust from the iron found in the meteorite.

The Wabar meteor is composed of iron and nickel. The alternate name

for this site is Hadida which is the Arabic word for iron. Even

before geologists understood the nature of this site, Bedouins had figured

out that it was a source of iron in the middle of the desert sands.

Hence, they named it Hadida.

Extensive fields of impactite and black glass surround the Wabar crater.

Sand dunes are gradually reclaiming the impact site. Wynn and

Shoemaker's article in 1998 Scientific American magazine states that the

largest crater was 12 meters deep in 1932, eight meters deep in 1961, and

nearly filled with sand by 1982. It won't be long in the geologic

time scale before Hadida disappears below the sands. If you want to

know more about the Wabar Crater and its geology, search Google for "The

Day the Sands Caught Fire" by Wynn and Shoemaker.

As the winds from the north deposit more sand in the Empty Quarter, the

Wabar Crater will eventually disappear beneath the dunes. The craters will

fill in and the impactite and black glass will be covered by advancing

dunes.

The big hole at Hadida is nice to look at, but don't ever drive your

Defender down into the hole. It will stay there forever because

there is no way to drive out.

Holes like this are a reminder to pay attention to what you are doing in

the dunes. Always look before you leap, because some mistakes are

forever. The further south you head in the Empty Quarter, the

bigger the dunes become. I have driven down slip faces that are more

than 200 feet high, and before you drive down, you better be 100 percent

sure that you are not descending into the pit of despair. It's hard

to imagine anything worse that leaving your Defender in the Empty Quarter

because you stupidly drove it into a hole.

On the trip back from Hadida, I had my opportunity

to lead the expedition into a sea of soft sand. It was high noon,

and I had no clue that in a few seconds I would be up to my chassis in

golden sand.

If I had a thousand dollars for every time I have been stuck, I would be a

millionaire.

I'm grateful for all the times I've been stuck over the years.

That's what happens when I live my dreams.

I've been up to my axles in sand hundreds of times.

That's terrific because it means I am living my sand dreams.

I've been stuck too many times to count, and I hope my good fortune

continues.

Life is good.

|