IF YOU TAKE CARE OF YOUR AUTOPILOT, IT WILL TAKE CARE OF YOU

Our autopilot steered Exit Only

99.9% of the way around the world. The only time we didn't use it was

for maneuvering in close quarters, and when we wanted to protect the

autopilot in rough seas.

In over 33,000 miles of sailing, we probably hand-steered the yacht less

than 100 hours. The autopilot holds a course better than any human

helmsman, it never got tired, and never complained. It essentially

functioned as another member of our crew. All we had to do was feed it

amps.

The Autohelm 7000 was reliable and tough. In eleven years of sailing

around the world, we experienced only two autopilot failures. The first

happened in French Polynesia where salt water intrusion destroyed a

motor bearing. The second problem happened sailing up the Great Barrier

Reef. In this instance, we stripped the epicyclic gears when the

autopilot made a maximum course correction, and the correction wasn't

enough, so it kept applying pressure to the gears until they stripped.

Those nylon gears had already sailed half way around the world, and when

they stripped, we replaced them with metal ones. The gears never

stripped again after we installed the brass ones.

When we sail offshore, we go to great lengths to protect our autopilot.

If the seas are extremely rough, we adjust our course and speed so that

the autopilot doesn't take a beating. A well-balanced sail plan makes

the autopilot's task easy, and poorly balanced sails are an invitation

to disaster. Smart sailors don't stress out their autopilots unless

there is a good reason.

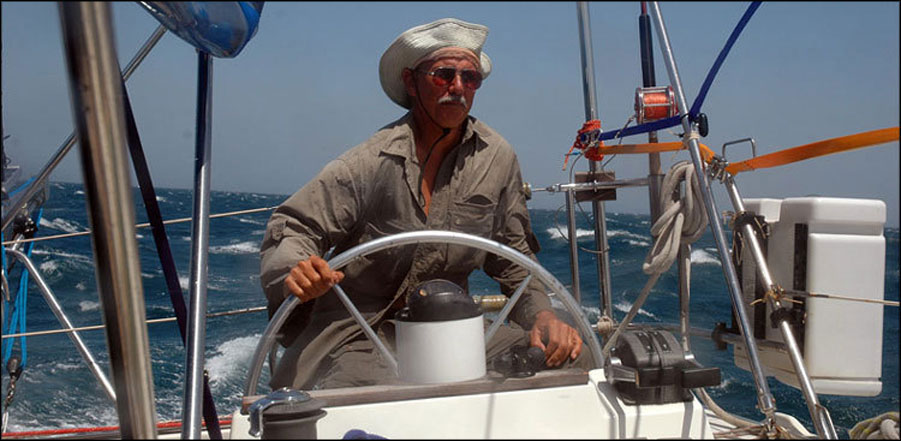

Take a look at Captain Dave at the helm in the Red Sea with 45 knots of

wind and quartering seas. We had just passed through the Bab Al Mandeb

at the southern end of the Red Sea and needed to sail about twenty miles

to tuck in behind a headland to escape the short steep seas and high

winds.

For three hours, I stood at the helm steering by hand, and in the

process, the salt spray turned my clothes into a pillar of salt. At the

end of the day, my clothes contained so much salt that they looked as

if they were starched; they could almost stand up without me in them.

The reason I stood at the helm for those three hours was because I

wanted to protect the autopilot. We had 1500 miles of remote Red Sea

cruising ahead of us, and it made sense to not risk the autopilot when

we had all those miles ahead. Hence, I steered by hand.

The autopilot probably would have handled the large quartering seas

without a problem. Nevertheless, three soaking wet hours at the helm is

a small price to pay to guarantee a functioning autopilot during the

rest of our Red Sea Adventure.

If instead of taking shelter, we had continued to sail directly down

wind and on through the night, I would have reduced sail, slowed the

boat down, and let the autopilot steer.

Protecting the autopilot is easy to do. If you balance your sails so

that you have a relatively neutral helm, you will put a smile on your

autopilot's face. When large unruly seas start pushing your boat around

and your speed accelerates to dangerous levels, simply slow your boat

down by reducing sail or towing warps or a drogue.

One of the easiest and best ways to protect your autopilot in rough seas

is to tow warps or use a drogue. Drogues and warps do two things to

make the autopilot's job easier. They slow the boat down and impart

greater directional stability to the vessel. Instead of your stern

slewing around in quartering or following seas, the drag devices tend to

hold your vessel on a steady heading. You don't get knocked around as

much, and your autopilot doesn't have to do as much work.

When we ran before steep

following seas sailing from Gibraltar to the Canaries, our drogues

slowed our speed down to four and a half knots, and kept us pointing

directly downwind. The autopilot didn't have a problem with the

following seas because of our high directional stability. When I am

towing a drogue or warps, the boat behaves as if it's much longer than

its designed waterline length. Instead of acting like a 39 foot

catamaran, it behaves like the warp or drogue are a part of the boat -

which in fact they are.

Protecting the autopilot is mostly common sense. If you make it easy

for your autopilot to survive and to steer, it will keep you safely on

course all the way around the world.

Real mariners know the sea, know their boat, and know their autopilot.

They treat their autopilot with respect; it sticks by their side though

thick and thin and perseveres when the rest of the crew have nothing

left to give.

Every sailor on board Exit Only knows that if they take care of the

autopilot, the autopilot will take care of them.

Click on

this button to tell your friends about this

website.

SURVIVING THE DANGER ZONES ON

BOARD EXIT ONLY

HIGH LIFELINES AND

SAFETY HALYARDS - HOW TO STAY ON BOARD OFFSHORE

Exit Only has an extremely safe cockpit for offshore sailing. As long

as the crew remains in the confines of the cockpit, there's little risk

of falling overboard.

The danger zone on board Exit Only is the area forward of the steering

wheels until you reach the safety of the amidships cap shrouds. If you

are moving or standing in that area and the catamaran is hit by a wave

and suddenly moves sideways, there's a significant risk you could fall

overboard. That's not just a theoretical risk. When we were in a storm

north of New Zealand, the boat was knocked eight feet sideways by a

wave, and one second I was standing in the middle of the salon, and the

next second I had fallen down into the galley. Boats sometimes get

knocked sideways, and if you are standing on deck when it happens, you

can instantly be thrown overboard.

That experience taught me a lesson. I decided to install high lifelines

that would protect the crew when we sailed offshore. I put those

lifelines in the danger zone, because that was the location of highest

risk.

When we started our circumnavigation, we had port and starboard

jacklines running the full length of the boat. I didn't like the wire

jacklines because stepping on them was like stepping on ball bearings.

They would roll under my foot and they could cause me to fall. I also

didn't like the fact that they had a white cover on them that made it

impossible to inspect the integrity of the wire. Hidden corrosion could

damage the jackline, and it could break just when you needed it most. I

have heard that in some countries it is illegal to use a white cover on

lifelines because you can't tell the status of the wire.

After several years, I replaced the wire jacklines with ones constructed

of webbing. Although the webbing worked fine, I worried about reports

of people falling overboard and being dragged through the water and

drowning because they were not strong enough to get back on board in a

water-logged state. Sometimes injuries prevented the overboard victim

from getting back on board, and in one case an elderly crew member

wasn't strong enough to pull her husband on board, and he drowned.

The jackline concept is good in theory, but in practice, it doesn't

always prevent you from going overboard. It doesn't prevent the safety

harness from breaking your ribs, it doesn't prevent fractures if you get

slammed into the side of the hull, and it doesn't get you back on board.

Our solution to the jackline problem was to install high lifelines that

ran at waist and shoulder height from the stern to the amidships cap

shrouds. These lifelines gave us protection in the danger zone.

We made our high lifelines using nylon webbing. We ran webbing back and

forth from the stern to the amidships shrouds to create a "spider web"

barrier that made it impossible to fall overboard. These high lifelines

were so secure that we would brace ourselves against them to stabilize

our cameras when shooting pictures offshore.

Once forward of the cap shrouds, we were out of the danger zone standing

at the mast with ten feet of deck between us and the deep blue sea. The

risk of falling overboard while standing at the mast was extremely

remote.

Whenever we sailed offshore, we installed the high lifelines to keep us

safe when going forward. At the end of the offshore passage, we took

the high lifelines down so that the webbing wouldn't be continually

exposed to the harmful effects of the sun's radiation.

Trampolines are the other danger zone on board Exit Only.

In rough seas north of New Zealand, we broke ten stainless steel

eyebolts that held sections of the trampolines in place. We discovered

the broken fasteners before anyone fell through the trampolines.

Falling through trampolines isn't a theoretical risk. Racer Rob James

was lost at sea after falling through the trampolines on his yacht.

Because of these and other foredeck risks, whenever crew goes forward to

work on deck or stand on the trampolines, we attach him to an extra long

spinnaker halyard that clips on to his safety harness. There's plenty

of slack in the halyard for the person to move around on the foredeck,

but if the crew member would go through the trampoline or fall

overboard, recovering them back on board simply involves winching them

on deck using the spinnaker halyard attached to their safety harness.

If someone falls through the trampoline on Exit Only, there's a good

chance that they will be able to save themselves with the spinnaker

halyard, and if that doesn't work, then a crew member will be able to

winch them on board.

Every yacht is a different design and has different danger zones. On

board Exit Only, high lifelines and an extra long spinnaker halyard

protect our crew when they are in the danger zones.

THE SEA IS SO BIG AND MY SHIP IS

SO SMALL

The last time I visited the Miami boat show,

I heard a prominent sailing magazine editor say that catamarans are only

seaworthy if they are more than forty feet in length. That came as a

big surprise to me, because I had already sailed Exit Only half way

around the world, and we were only thirty-nine and a half feet long.

According to his gospel, we were circumnavigating the world in a barely

seaworthy vessel.

I have more than 33,000 miles of offshore sailing under my belt, and I

can unequivocally say that size has little to do with seaworthiness. A

sturdy small yacht that's sailed well is far more seaworthy than a large

vessel sailed poorly by an inexperienced crew.

I know of a 32 foot catamaran that rounded Cape Horn, and I met sailors

in Thailand who were completing a circumnavigation on a 35 foot

catamaran with a crew of three.

So what's the difference between maxi cats and small cats like Exit

Only? It doesn't have much to do with seaworthiness; it's more about

speed and the ability to carry weight. Big cats go faster, sometimes a

lot faster, and they can carry more weight. Fast is good, but usually

not that important. If you're really into speed, you should be flying

in a 747, after all, nothing goes to windward like a 747.

High speed is a mixed blessing. Sailing at fifteen to twenty knots is

exciting and may give you the ability to get out of harms way when

you're running from a storm. But the speed that can save you can also

be your undoing. What do I mean by that?

When I sail Exit Only at six knots, my

margin for error is infinitely large, but when I am sailing at twenty

knots the margin for error is razor thin. I once saw our speedometer

max out at eighteen knots during an Atlantic storm as we sailed from

Gibraltar to the Canary Islands, and I was more than a little

concerned. If the autopilot failed or any significant problem happened

at that speed, my catamaran could capsize or suffer structural damage.

There was no margin for error, and it was mandatory that I decrease our

speed to safe levels. I trailed two warps behind Exit Only bringing our

speed down to four and a half knots, and immediately smiles broke out

among the crew. In spite of the twenty foot seas, Exit Only was sailing

at a safe speed with a comfortable motion, and we knew that we would be

ok. We spent the next two days running off in thirty five to forty

knots of wind without a problem. We were out of the danger zone and

into the "No Worries Mate" zone.

No matter what the size of your cat, you can't maintain high speeds for

long periods without incurring structural damage. It's simply a matter

of physics. The hull structure simply can't safely dissipate all the

kinetic energy associated with high speeds for an unlimited period of

time. If you push a large high tech cat too fast for too long in large

seas, a demolition derby begins. I've seen fast cats sitting high and

dry in boatyards around the world awaiting repairs. If you want to

discover the structural weakness in your cat, just sail it fast in big

seas, and it won't be long before you find the weakest link in your

speed machine.

Seaworthiness isn't about size; its about seamanship. You must know the

sea, and know your vessel, and sail it in a manner that it makes it

possible to survive.

I sail my catamaran at five to six knots around the clock when I am

offshore. I move at those speeds so that my crew is comfortable, and

the boat has a reasonable motion. At six knots my autopilot

effortlessly handles the wind and seas, and everyone knows they are

safe. When boat speed goes above ten knots, everyone becomes uneasy,

because we are sailing closer to the edge.

Our perfect boat speed is 6.25 knots. At that speed Exit Only is able

to click off one-hundred fifty miles per day and do it in comfort

without risk. Equally important, the autopilot is happy, and a happy

autopilot means a happy crew.

When you're sailing fast in big seas, the load on the autopilot

increases substantially. That's not a problem until you strip the gears

on the autopilot or burn out its motor. Then you have a real problem,

because suddenly you must hand steer in bad weather, and if you are

crossing an ocean, you might be hand steering for several weeks. When

the wind and sea state increase, I sail in damage control mode to

protect my autopilot, because I want my autopilot to live long and

prosper.

Yacht designers and salesman worship at the altar of speed, while most

cruisers worship at the altar of safety and comfort. If you are a

mariner versed in the ways of the sea, you know the truth about

seaworthiness. It's not the size of the vessel that matters; it's how

you sail it that really counts. So don't let anyone tell you that your

vessel is unseaworthy because of it's size. Just look them in the eye,

and wave good-bye as you start your voyage around the world.

Although the sea is big, and my ship is small, life is still good.