DOUBLE HEADSAIL DOWNWIND SAILING

Multihulls are superb yachts for

sailing downwind around the world. They are an extremely stable sailing

platform that does not roll as the yacht sails directly downwind. The

big question is, "What is the best sail rig for downwind sailing?"

Cruising multihulls making offshore passages haven't been around that

long, and many people carry their monohull biases into the multihull

world. The fact is, multihull performance and behavior are so different

from monohulls that you need to have a new and different way of thinking

about how you sail a multihull offshore.

A good example of this is downwind sailing.

When I first started sailing downwind around the world, I absolutely

drove myself crazy trying to run downwind wing and wing. My monohull

brain said that I should vang the main out on one side of the yacht and

the headsail out on the other side of the yacht, and life would be

perfect as I sailed downwind to paradise.

Unfortunately, things didn't work that way on the high seas. There were

several reasons.

1. We didn't have backstays like a monohull. Instead, we had cap shrouds

that came back about 2/3 of the way aft. That meant that I could not get

the mainsail as far forward and as flat as I wanted to sail downwind.

The capshrouds were in the way.

2. I had diamond stays on the mast to hold the mast in column. When I

tried to sail wing and wing, the mainsail would chafe on the spreaders

that had a backward bias in their positioning. I didn't like that chafe.

3. The mainsail on a catamaran is extremely large with an equally large

roach, so in the wing and wing configuration, the main tried to

overpower the headsail, and we tended to round up into the wind. Someone

had to be watching things like a hawk to keep everything in balance. If

you reefed the mainsail so that it had less power, and the headsail

overpowered the yacht, then you could have an unintentional gybe.

4. Because of the tendency to round up created by the battle between the

mainsail and headsail, you had to pay attention to sail balance all the

time. If the mainsail overpowered the boat and we rounded up into the

wind, then the Autohelm 7000 joined into the fray and tried to bring the

boat back on course. If the autopilot made a maximal correction and the

boat didn't get back on course, the autopilot tried even harder to do

it's job until it stripped out the epicyclic gear on the autopilot. So

if we did the wing and wing sail combination, someone had to sit in the

cockpit and watch the autopilot, the sails, and the seas to make sure

everything stayed under control, and the autopilot didn't destroy

itself. We only stripped the epicyclic gears one time during our

circumnavigation, but we learned our lesson. Don't put the autopilot in

a position where it is at a massive disadvantage, and you will keep a

smile on the face of the autopilot.

We left Fort Lauderdale on our circumnavigation with our monohull brains

forcing us into the wing and wing sail pattern. By the time we arrived

in Panama, we realized that we needed to have something that worked

better downwind. We figured out that we needed (horror of horrors) two

spinnaker poles and a double headsail rig.

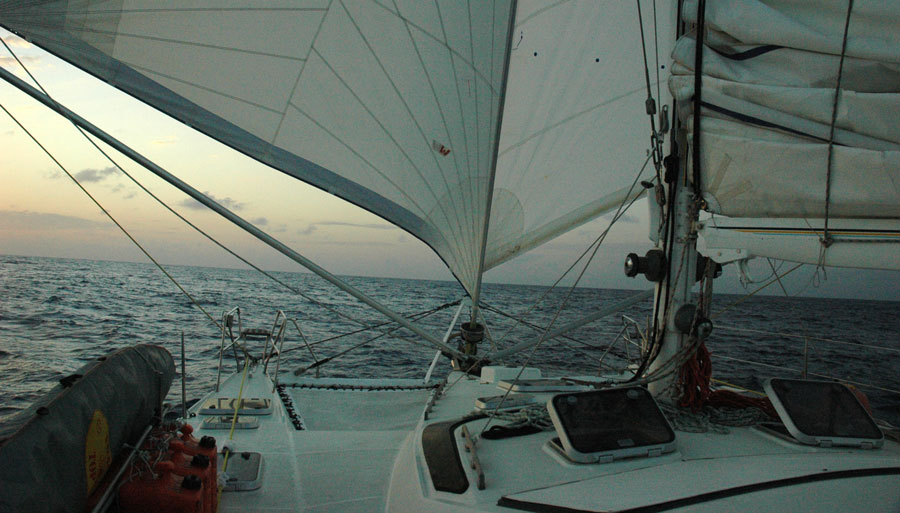

Once we put out two spinnaker poles and double headsails, and doused the

main, our life instantly improved. Words like "awesome", "unbelievable",

and "it doesn't get any better than this", popped into our minds.

Click on

this button to tell your friends about "Double Headsail Downwind

Sailing".

Sailing downwind with a double headsail rig was a dream come true.

Nobody needed to watch the mainsail. There were no chafe problems with

the mainsail rubbing against rigging and spreaders. The autopilot was

supremely happy because the center of effort was at the bow of the boat,

and the autopilot no longer had to battle the mainsail. There was a

permanent smile on our autopilot's face as we sailed downwind around the

world.

When we started our

circumnavigation, we decided that we wanted to do it the easy way. We

would sail around the world in the trade winds.

Of course, it's impossible to go all the way around the world in the

trades, but for the majority of the long passages, it's possible to sail

in the trades.

Five-hundred years ago, sailors knew that the trade winds were their

friends. Whenever possible, they headed for the trades to get the

horsepower they needed for their global adventures. Although ocean

voyaging has changed a lot since the days of the square-riggers, trade

wind sailing remains unchanged. When we wish sailors well, we still

say, "Fair winds and following seas." That means only one thing - winds

and seas abaft the beam.

Catamarans are excellent trade wind yachts. They can sail directly

downwind without the rolling that plagues monohull yachts. Catamarans

travel like they are on railroad tracks when sailed like a square-rigger

downwind.

The fore and aft rig is a problem when running directly downwind. When

you run wing and wing, the mainsail and genoa continually battle for

supremacy. If the mainsail wins, the boat rounds up into the wind, and

if the headsail wins, you sometimes experience an unwanted, uncontrolled

jibe. It's hard to balance the mainsail and genoa in the wing and wing

configuration. The crew continually has to stay on top of the sail

balance and make helm adjustments to keep things under control.

The battle between the genoa and mainsail isn't so bad if you don't mind

standing eternally at the helm staring at the sails. You can sail wing

and wing forever if you have a large, competent crew. But if you want

to use the autopilot, the wing and wing configuration can cause

problems. Out of balance sails can overwhelm the autopilot, and if you

are unlucky, the autopilot will strip its gears while attempting to get

the boat back on course.

When I sail offshore, my first priority is to keep my crew out of harm's

way, and my second priority is to protect the autopilot. Our autopilot

steered Exit Only 99% of the way around the world, and I hold our

autopilot in high regard. On only one occasion on our circumnavigation,

our autopilot was overwhelmed by a full mainsail in following seas, and

the autopilot made a valiant attempt at correcting our course, and

instead succeeded in stripping its epicyclic gears.

When the autopilot attempts to make a course correction without success,

it doesn't stop trying. It just keeps putting pressure on the gears,

and finally the motor overwhelms the gears and strips them.

I stay away from the wing and wing configuration on Exit Only because I

want to protect my autopilot. I also stay away from it because a double

headsail rig works much better on a catamaran.

When I sail downwind in the trade winds, I don't use my mainsail.

Instead, I sail using two genoas held out by two eighteen foot spinnaker

poles. One of the genoas is attached to the roller-furler, and the

other is flown with a free-standing luff.

This double-headsail rig moves the center of effort of the sails all the

way forward to the bow, Exit Only glides smoothly over the waves, and

the autopilot has a smile on its face. With the double-headsail

downwind rig, lee helm and weather helm aren't a problem. The helm

remains neutral, and the autopilot easily makes small course corrections

as we sail downwind.

The double headsail rig is so stable, and the helm is so balanced that I

can recline in the comfort our mainsail while the autopilot holds

us on course as I live my trade wind dreams..

When we sailed across the Atlantic, we used our double-headsail rig all

the way to Barbados. The rig is easy to set up and take down.

Before we leave port, we fix our spinnaker poles in position using a

topping life, a foreguy and an afterguy. We leave those poles up all

the way across the Atlantic. The poles serve a triple purpose.

First, they keep the sails out in front of

Exit Only at the level of the bows.

Second, they keep the headsails quiet.

Third, they allow us to carry the double

headsail rig until the wind moves forward almost to the beam.

Keeping the sails out in front of the bows keeps the center of effort of

the sails forward and balanced which makes it easy for the autopilot to

steer downwind.

Keeping the sails quiet is a big help to the person on watch. He

doesn't need to continually look at a thousand square feet of white sail

in front of his eyes to tell what's happening. He only needs to listen

with his ears. If the sails are starting to flutter, the wind has moved

forward, and it's time to adjust the course. If the sails are quiet,

it's time to keep on trucking.

The poles make it possible for the wind to move around a great deal

without having to make major course adjustments. You don't need to be

sailing directly downwind for the rig to work. As long as the wind

stays twenty degrees abaft the beam, you can carry the downwind rig.

We have one headsail on a Profurl roller-furler, and the second

identical headsail flies with a free standing luff. We roll the Profurl

headsail in and out according to how hard the trades are blowing. The

Profurl sail is like a throttle that we adjust to control our speed and

the amount of stress on our rigging.

If the wind becomes too strong and we want to take down the

free-standing genoa, we unroll the Profurl on the same side of the boat

as the free standing genoa to blanket it. Then we can easily take down

the genoa without having to battle a flogging sail. It would be easier

to have two Profurl roller furling headsails, but that would cost a lot

more money and require modifications to the mast and rigging. So we do

it the less expensive way which is a little more work.

If the trade winds blow really hard, we use only one headsail; we roll

the Profurl in and out to suit the prevailing conditions.

It's more fun to go sailing when you do no bruising cruising. It's more

fun to sail downwind when you have a balanced helm. It's more fun to

cross oceans when the autopilot steers the boat. That's why we sail in

a catamaran and use a double-headsail downwind rig.

Life is good.

GRAND SCHEMES AND OTHER IMPORTANT THINGS

In the grand scheme of things, my grand

schemes seem fairly insignificant. In a global sense it's easy to feel

as if my life counts for nothing, or at most, counts for little.

I've had several earnest people tell me in no uncertain terms that I was

wasting my life as I sailed around the world on my yacht, and I can

understand why they felt that way. Those people thought I was on a

prolonged vacation, and they didn't understand that I was making a life

and doing things that were important to me. They couldn't see that I

was giving my children a multicultural experience that made them into

citizens of the world. We didn't just sail around the world, WE

SAILED AROUND THE WORLD AS A FAMILY . In the age of single parent

families we were doing things the old fashioned way - we were a real

deal family unit in which every person on board had responsibilities

that contributed to a safe voyage. My children survived without cell

phones and a dreaded peer group to complicate their lives, and they grew

up to be good citizens of the world who actually cared about other

people - even people from the third world.

During that eleven year voyage, I maintained the yacht, wrote five

books, started three web sites, and paid for my children's college

education. There weren't enough hours in a day to do all the important

things that demanded my attention. Now that I have sailed around the

world, I can finally take a real vacation from all of that work.

A long time ago I learned that what

other people think of me is none of my business, and I focused on doing

what was important to me. Life is an inside job that works best when I

start from the inside and work my way out. When someone tells me that I

shouldn't be doing things that are important to me, and that I'm wasting

my life, they are really saying that my dreams don't count in their

scheme of things. My dreams aren't important, and instead, I should

live dreams that make sense to them. These people are Outside-Inners

because they are taking their outside dreams and trying to cram them

down my throat, and that doesn't work. It's the recipe for anger and

frustration, and is a terrible way to make a life.

In the grand scheme of things, my grand schemes are supremely important

to me and to me alone. I have a choice. I can either live my dreams,

not worrying about what other people think, or I can forget my dreams,

and let them wither. If I do that, my spirit will wither as well. Joy

will no longer spring up in my heart, and each step I take will echo the

dull thud of dread I feel in my heart that results from not living my

dreams.

The handwriting is on the wall, and the message is clear. There is

simply nothing more important than living my dreams. Even if I don't

rock the world, I can still rock my world and that's what counts.

Someone much smarter than me said, "What you do isn't important, but

it's important that you do it." Those words have the ring of truth, and

you can build your life on them. So fire up your dream machine and have

a few grand schemes of your own, because that's why you're here on

planet earth. God gave you the capacity to dream, and He gave you a

lifetime to make those dreams come true.

Please excuse me. I must go now because it's time to work on my grand

schemes.

Click on

this button to tell your friends about

Grand Schemes And Other Important Things.

RIGGING EMERGENCY AVERTED: YOUR SAILBOAT

IS TALKING TO YOU, BUT ARE YOU LISTENING?

David and I are sitting on the lower

spreaders of Exit Only, and we are taking care of business. Although we

survived the trip up the Red Sea during the previous two months, we took

quite a beating in the Gulf of Suez. We didn't know how much of a

beating it was until we hauled out in Turkey and checked the rigging.

What we found was scary.

A stainless steel strap toggle holding the headstay in place had

apparently broken during the Red Sea transit. We were extremely

fortunate that we didn't loose our mast as we slogged up the Red Sea. A

Turkish craftsman fashioned a new strap toggle out of stainless steel,

and we installed it to prevent the mast from going over the side at

sea. We truly snatched victory from the jaws of disaster.

After discovering the failure in the headstay strap toggle, we decided

to climb the mast and inspect all of the rigging. The inspection found

broken strands of wire in an eight millimeter diamond shroud. Rigging

problems seemed to be coming down like rain, but at least we weren't off

shore when it happened. I wasn't too upset, because it's always better

to deal with rigging problems while I'm in safe harbor than when I'm in

forty knots of wind offshore and could easily lose the mast.

Losing a mast is expensive. Without insurance, such a disaster could

cost upwards of twenty thousand dollars if you do all the work

yourself. If you hired it done with labor rates at seventy-five dollars

an hour, your cruising kitty would instantly implode.

If I lose my mast, I lose the ten thousand dollar deductible on my yacht

insurance. That's a huge chunk of cash to lay out for a problem that's

probably preventable. Before I sail offshore, I always climb to the top

of the mast and check every piece of rigging to make sure there's no

problem. It's a hassle to put on a climbing harness and do a tap dance

up the mast, but it's not nearly as unpleasant as dealing with a

dismasting at sea. In my time aloft I've identified broken strands of

stainless steel wire on at least ten occasions, and the few minutes

spent climbing the mast have paid off in a big way.

Sailboats are always talking to you. Sometimes they whisper, and other

times they shout. When you go aloft and find a tiny fractured strand of

rigging wire, your yachts is whispering a warning. "Fix me while it's

cheap and easy." If you wait until your yacht shouts at you, it's going

to be screaming things you don't want to hear. You'll be hearing words

like, "You really messed up this time. Why didn't you check my rigging

before you sailed offshore. Now my mast is in water and it's going to

cost you a ton of money. How could something like this happen when you

call yourself a mariner?"

We have sailed over thirty-three thousand miles around the world, and

during our voyage we replaced damaged rigging in Bora Bora, Fiji, New

Zealand, Australia, Turkey, and Gibraltar. In each instance, we

discovered a problem and dealt with it before it became an emergency.

That's the way mariners get their yacht around the world. Eternal

vigilance is our best friend and beats good luck seven days of the week.

There's an old saying, "The harder I work, the luckier I get." I would

recommend that every mariner carve those words into their main bulkhead,

get them tattooed on their forearm, and have their wife repeat them at

least seven times a day. If you want to sail around the world, you must

work hard to push the odds in your favor. Good luck isn't going to keep

your mast upright where it belongs. You're the only one who can make

that happen.

You earn the right to sail on the ocean of your dreams by taking good

care of your yacht. When you take care of it, it takes care of you.

Life is good.

DON'T HESITATE! TAKE THE

PLUNGE NOW AND ORDER

THE RED SEA

CHRONICLES. JUMP INTO A

GREAT MULTIHULL CRUISING DVD. YOU WILL BE GLAD THAT YOU DID!