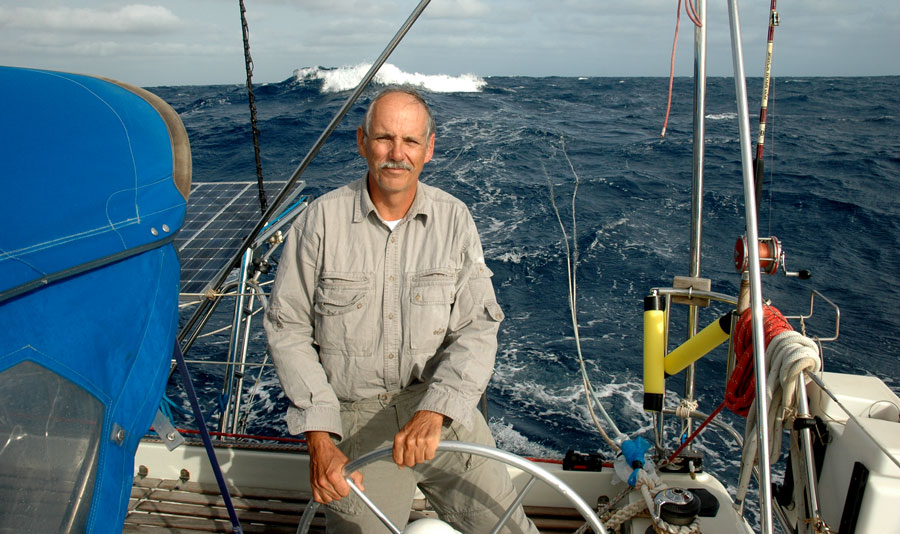

SURVIVING THE SAVAGE SEAS

Once upon a time there was a small catamaran

named Exit Only. Although it wasn't a large yacht, it was big enough to

sail the seven seas - the reason was simple. Ninety-five percent of the

time the seas were small and the winds were light. In fact, in an

eleven year voyage around the world, Exit Only never saw winds in excess

of fifty knots while on passage, and only three or four times saw winds

up to forty knots.

That's the way it is for most boats who sail in temperate latitudes at

the correct time of year. People who sail for pleasure, rather than

necessity or racing, rarely find themselves caught out in a gale.

Nevertheless, sometimes mother nature throws you a curve and you get

caught in a storm, and that's exactly what happened to us as we ventured

out into the Atlantic from Gibraltar.

We

started our transatlantic crossing by sailing from Gibraltar to the

Canary Islands. Because this passage takes only five to six days, we

were able to select our weather window at the beginning of the trip, but

during the end of the passage the weather was up for grabs. We had no

reason to expect it would be bad, and no guarantee it would remain good.

As

the weather gods would have it, the last three days of the trip turned

into a gale with winds gusting to forty knots. Fortunately, the winds

were coming primarily from behind so we could run downwind.

Unfortunately, the seas rapidly became steep, up to twenty feet in

height, and there were cross seas as well, creating an exciting and

potentially dangerous ride.

Why

is it dangerous to sail downwind in gale force winds? Think for a

moment about the last time you saw a surfer wipeout going down the front

of a twenty foot wave. He has an awesome ride right up to the moment he

and his surfboard go berserk and get pulverized in the surf. Words like

pain and disaster pop into your mind as you watch the spectacular

wipeout.

Similar things can happen to a cruising yacht when it surfs down the

waves during a gale. When Exit Only started rocketing down those steep

twenty foot seas, our speed peaked at eighteen knots. Exit Only became

a giant surfboard that was forty feet long and twenty-one feet wide.

Surfing at ten knots was fun. Surfing at eighteen knots was getting

close to wipeout speed. If the autopilot lost control of the boat

during an eighteen knot surf, disaster could happen. Wipeout in a

cruising catamaran means flipping it over - a very expensive and painful

mistake - not to mention the fact the crew can get badly hurt in a

capsize. When your catamaran is upside down in the ocean, it becomes

the most expensive life raft on the seven seas.

Click on this button to

tell your friends about "Surviving The Savage Seas".

So

what do you do when things are getting out of control and you are

approaching wipeout conditions? The first thing to do is slow the boat

down by reducing sail. We had already done that. Our mainsail was

furled, and we had about ten percent of our headsail out to give us

enough sail power forward to keep our autopilot happy and make it easy

to safely steer the yacht downwind. That small handkerchief of sail

kept our boat pointed downwind, but it still gave us too much speed

which was getting out of control.

Taking our foot off the accelerator by reducing sail wasn't enough. We

needed to apply the brakes, and that's exactly what we did. Once we

turned on our boat breaks, our speed came down to five or six knots, and

peace and serenity returned to our chaotic water world.

What

exactly are boat brakes, and how do you apply them? Boat brakes are

drogues that you trail behind your boat to slow down. There are many

types of drogues, and you can trail them in many different

configurations.

The

main criteria for success in using drogues is they reduce your speed to

a safe level. You have enough speed for the autopilot to easily steer

the yacht, but you don't want to slow down so much that waves break on

the stern and fill your cockpit with water. Putting on boat brakes

isn't rocket science - just common sense.

Each

yacht behaves differently in following seas, and the number and type of

drogues you use depends on the design of the yacht. It's mostly trial

and error. The first drogue we put out consisted of eighty feet of one

inch three strand nylon rope with a ball of anchor chain attached to its

middle. We took fifteen feet of three-eighths inch chain and tied it in

knots and shackled it to a swivel in the middle of the rope bridle. We

then attached the two ends of the bridle to port and starboard winches

at the back of Exit Only. This first drogue had a modest effect in

slowing us down most of the time, but on the really big surfs, it didn't

give us enough drag.

We

put out a second drogue consisting of one-hundred and eighty feet of one

inch nylon line which formed a giant loop behind the boat, and we also

attached it to the winches at the back of the boat. This slowed us down

further, but still not quite enough. I increased the effectiveness of

this drogue by putting PVC hose on the line, and I shackled the dingy

anchor and chain to the hose. The PVC hose was a messenger that

transported the anchor and chain down the line, and carried it all the

way to the back of the one-hundred and eighty foot rope loop. This

additional weight kept the long loop of rope continually submerged and

substantially increased the effectiveness of the second drogue in

controlling boat speed. This was just right.

We

ended up trailing two drogues behind our boat. One loop trailed forty

feet behind Exit Only, and the other was eighty feet off our stern. The

weights on the drogues kept them submerged, and the different distances

of the drogues from the stern guaranteed that one of them was effective

when the other was slack. This combination of drogues snatched victory

from the jaws of defeat, and our worries were over.

If

the storm became worse, we would have deployed our Jordan Series Drogue

which consists of a two-hundred foot line with one-hundred and twenty

sailcloth cones attached to the line. That would have stopped us in our

tracks. Fortunately, we didn't need a drogue that powerful, so we

didn't use it. It was ready if we needed it, but thankfully, it wasn't

necessary.

These storm management techniques worked well for us because we are a

catamaran. The arms of the drogues were attached to winches that are

twenty feet apart on the stern, and that augmented the ability of the

drogue to create directional stability in the yacht. It also worked

well because a catamaran has a bridge deck, and when breaking seas

assault the stern of Exit Only, they pass under the bridge deck rather

than come into the cockpit. On a monohull yacht, the same techniques

might be less effective, and you might end up with water in the

cockpit. Every yacht behaves in a different manner when they trail

drogues in steep following seas. Several monohull yachts sailing in the

same gale ended up with water in their cockpit.

In

33,000 miles of sailing around the world, this was the first time we

ever needed to trail drogues behind our yacht. That should put things

in their proper perspective. If you sail the seven seas in a

conservative manner at the correct time of year, you have a ninety-five

percent chance of having a wonderful adventure, but five percent of the

time, things may unwind a bit, and you end up in a gale. When that

happens, you say, "No worries mate." You trail your drogues and control

your speed until the storm passes by. Then you continue on to your

destination and tell your friends about how you survived the savage

seas.

Boat brakes. I love them!

ABBOTT DROGUE - ADJUSTABLE

MEDIUM PULL DROGUE FOR WINDS TO FIFTY KNOTS

INEXPENSIVE

DROGUE THAT YOU CAN CONSTRUCT USING MATERIALS ONBOARD

Most storms at sea are not survival storms, and you don't need to

put out a parachute sea anchor or use a Jordan Series Drogue to

survive. What you need is help controlling your yacht in non-survival

conditions.

Even though most yachts don't experience survival storms, many still

get out of control and broach because they sail in an uncontrolled

manner. These yachts need something to slow them down and impart

directional stability to their vessel to remain in control in bad

weather.

On Exit Only, we use an ABBOTT DROGUE constructed of materials that

are readily available on board. We don't need to get out the Series

Drogue because the ABBOTT DROGUE HAS ENOUGH POWER to control our 39 foot

catamaran in winds up to fifty knots. In our eleven year

circumnavigation we never had winds in excess of fifty knots, and we

never had to use our Series Drogue.

The

ABBOTT DROGUE consists of one-hundred and eighty feet of one inch nylon

line which forms a giant loop behind the boat. We attach the loops to

the port and starboard winches at the back of the boat. We then slide

weights down the loop of rope to increase the drogue effect.

You can't slide weights down a warp without attaching them to a carrier

(to prevent chafe), and I use water hose as my carrier that transports

the weights down the warp. I slide a meter long piece of flexible

plastic water hose over the one inch warp , and then I shackle the dingy

anchor and chain to the water hose so that it's firmly attached , and it

cannot come off the hose carrier. The hose is the carrier that

transports the anchor and chain down the warp to the center of the

one-hundred and eighty foot rope loop. As soon as the carrier and

attached weight hit the water, they slide rapidly down the warp until

they reach the middle of the loop, This additional weight keeps the

warp continually submerged and substantially increases the effectiveness

of the warp in controlling boat speed. The irregular shape and heavy

weight of the chain and dingy anchor on the carrier creates turbulence

in the water increasing the power of the drogue.

The ABBOTT DROGUE has several advantages.

1. It is adjustable. You can winch the drogue in and out to

control its distance behind your yacht. If you want the drogue farther

out, let out more line. If you want the drogue closer to the yacht,

then winch it in. It's a good idea to vary the distance of the drogue

behind the yacht according the the sea state. You don't want the drogue

to pull out of the front side of a wave which would cause it to

instantly lose it's effectiveness. Instead, you want the drogue in the

middle or the backside of the wave where it will have maximum power.

This is easily done by adjusting the length of the rope loop.

2. The carriers stay centered in the middle of the rope loop where

it has maximum effectiveness.

3. You can vary the power of the drogue. You can send as many

hose carriers down the warp as you want. If you want to increase the

power of the drogue, then put more anchor chain on the hose carriers and

send a second or third carrier down the warp to the back of the loop.

4. It is chafe resistant. We normally use hose on our boat as

chafing gear for our dock lines. We use the same water hose as the

carriers to carry the weights out to the middle of the loop of rope. If

we are worried about chafe in a storm, we can take in or let out a

little more rope so that the position of the carriers on the warp shift

slightly reducing any chafe.

5. It's easily recoverable. When it comes time to pull in the

ABBOTT DROGUE, you simply winch it in. Because the hose carriers stay

centered in the middle of the rope loop, the carriers and attached

weights are easy to recover when they get to the stern of the yacht.

6. It's constructed of materials that you already have on board.

You don't need to spend a thousand dollars to have an ABBOTT DROGUE.

You simply use water hose for carriers, anchors and chains for weight,

and warps that you already have on board.

The ABBOTT DROGUE works well for us because

we are a catamaran. The arms of the drogues are attached to winches

that are twenty feet apart on the stern, and that augments the ability

of the drogue to create directional stability in our yacht. It also

works well because a catamaran has a bridge deck, and when breaking seas

assault the stern of Exit Only, they tend to pass under the bridge deck

rather than come into the cockpit. On a monohull yacht, the same

techniques might be less effective, and you might end up with water in

the cockpit. Every yacht behaves in a different manner when they trail

drogues in steep following seas.

An ABBOTT DROGUE isn't a Jordan Series Drogue, and it's not intended to

be used in survival conditions.

The ABBOTT DROGUE is a medium pull drogue intended for use in winds to

fifty knots. It's easily constructed in an emergency, adjustable, chafe

resistant, and inexpensive.

When we find ourselves in trouble offshore, but not in survival

conditions, we construct an ABBOTT DROGUE. If conditions deteriorate

further, then we call upon our Jordan Series Drogue or Parachute Sea

Anchor to keep us safe.

Life is good.

YOU MUST KNOW THE SEA

Joshua Slocum said, "You must know

the sea, and know that you know it, and know that it was meant

to be sailed upon." What Joshua was describing was a real

mariner.

True mariners are in short supply. There have never been so

many boats parked in marinas, and so few mariners to take them

out of the slip.

The ocean is a mariner factory. When you successfully weather a

storm at sea, you're one storm closer to becoming a true

mariner. Surviving a single storm at sea may not make you into

a mariner, but it's a step in the right direction.

Becoming a mariner takes time, because it requires years to get

to know the sea in all of its moods. You can't get to know it

from books. You can read about it all you want, but until you

experience it first hand, you won't understand the wiles of the

sea. You need to put thousands of miles in your wake before you

know the sea and know that you know it.

I've

been to seminars designed to prepare sailors for offshore sailing.

Seminars are good at teaching people what to do in an emergency, but

there's no seminar that can make you into a mariner. Only the sea can

do that.

Becoming a mariner is a catch-22 situation. You shouldn't go to sea

unless you are a mariner, and you can't become a mariner unless you go

to sea.

The wannabe mariner's dilemma isn't as bad as it first might seem.

Becoming a mariner is an incremental task, and most of all, you need

time at sea. There's no other way to become a mariner except by

slipping your dock lines and getting out on the high seas. The trick is

to not bite off more than you can chew early on in the process.

When I first set sail on my circumnavigation, I had never sailed

offshore at night. I was comfortable with the idea of sailing during

daylight hours, but night sailing was an entirely different matter. I

felt as if I was sailing blind and it made me uneasy. I had to start

thinking like a mariner about night sailing. I quickly discovered that

if I reduced sail and slowed the boat down at night, my distaste for

night sailing went away. Slowing down at night was one of the first

mariner-like lessons I learned on my trip around the world.

The sea has many lessons to teach, and if we pay attention, it won't be

long before we start behaving like mariners. Our sea legs will come,

and eventually we will learn to swashbuckle with confidence as we sail

the seven seas.

Knowing the sea, and knowing that you know it, isn't impossible, it just

takes time. If you are patient and put in the time, your confidence

will increase, and you will know that the sea was meant to sailed upon.

You will become a true mariner.

TAKE THE PLUNGE AND

ORDER THE

RED SEA CHRONICLES.

JUMP INTO A GREAT MULTIHULL CRUISING VIDEO. YOU WILL BE GLAD THAT

YOU DID!